I am a collector.

I have a unique collection of trench art marked with names and service numbers.

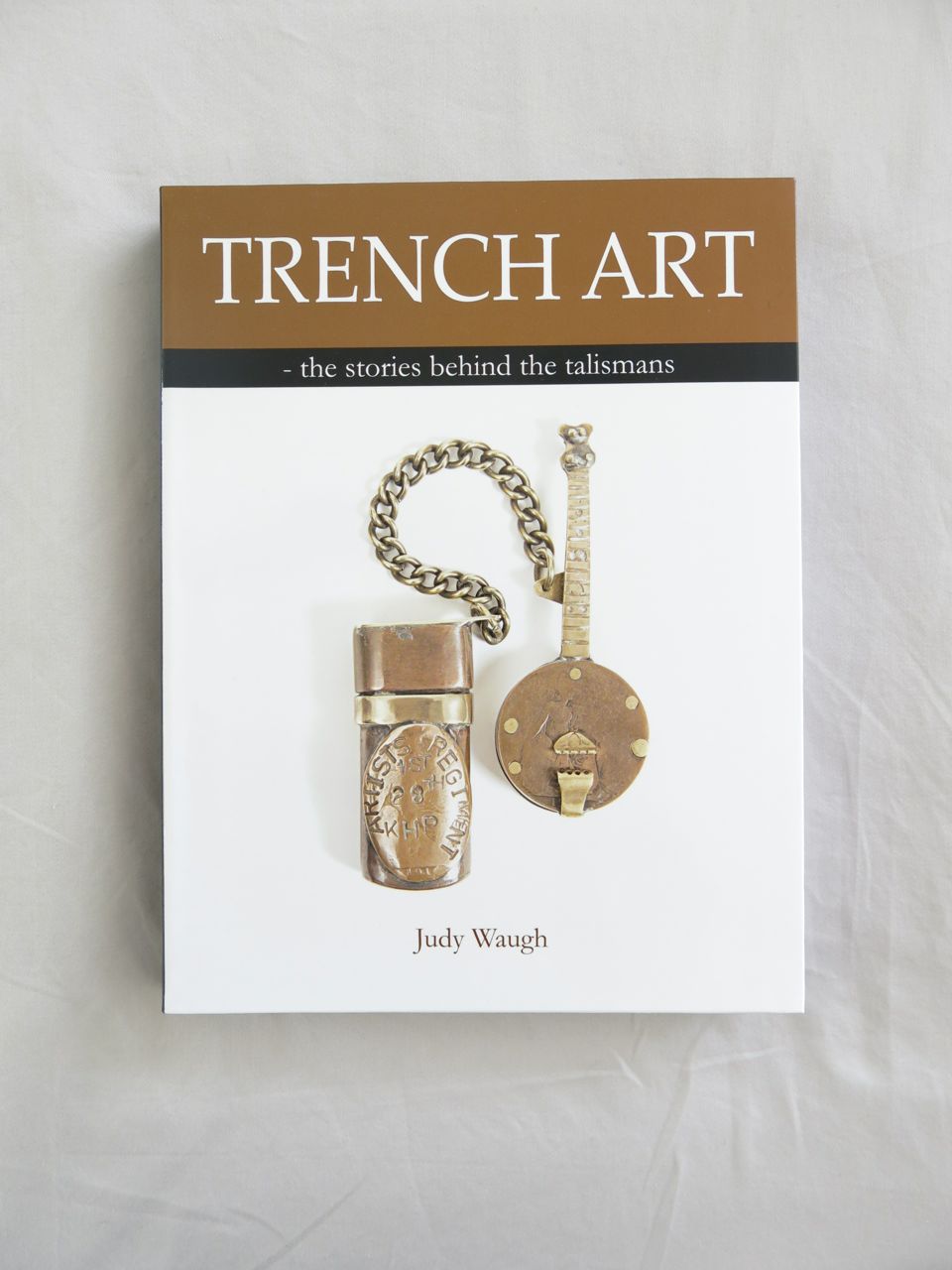

My book TRENCH ART was published in Australia on Remembrance Day 2015. The early chapters of the book are below, explaining how I came by the collection, who photographed it, and why I felt compelled to tell the stories.

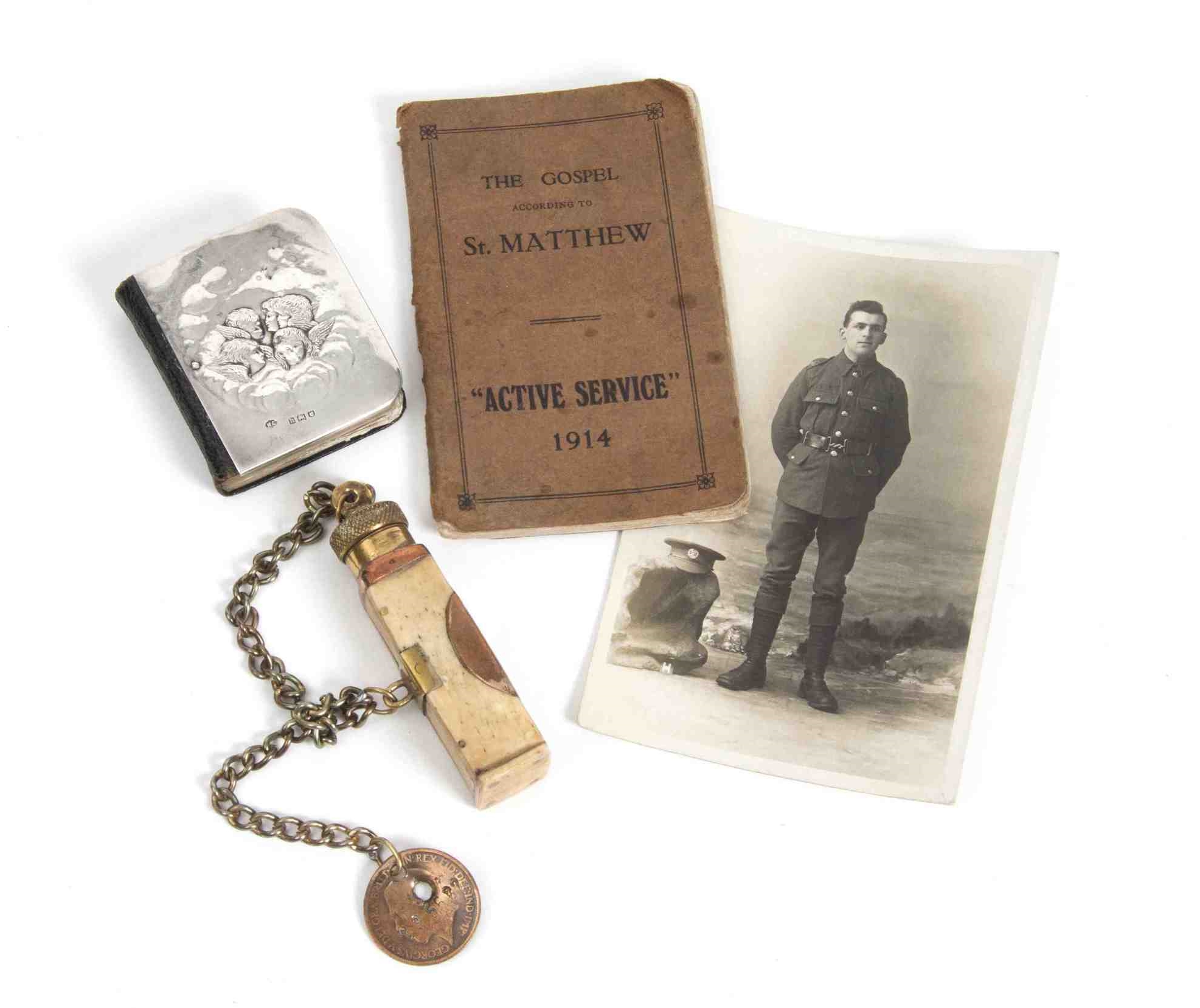

57 pieces are from WW1, shown below. Most belonged to young men who were killed in action or died of their wounds - on the Somme, at Gallipoli, in Egypt and Palestine, and Mesopotamia. In the book, I have told their stories.

It’s not important whether the soldiers made them for themselves. What is important is the symbolism that they chose to cling to, both physically and metaphorically, as they faced the unknown - symbols of music and home and loved ones, of honour and duty, and faith.

I became fascinated by this - the power to choose what to think about in times of trauma.

_____

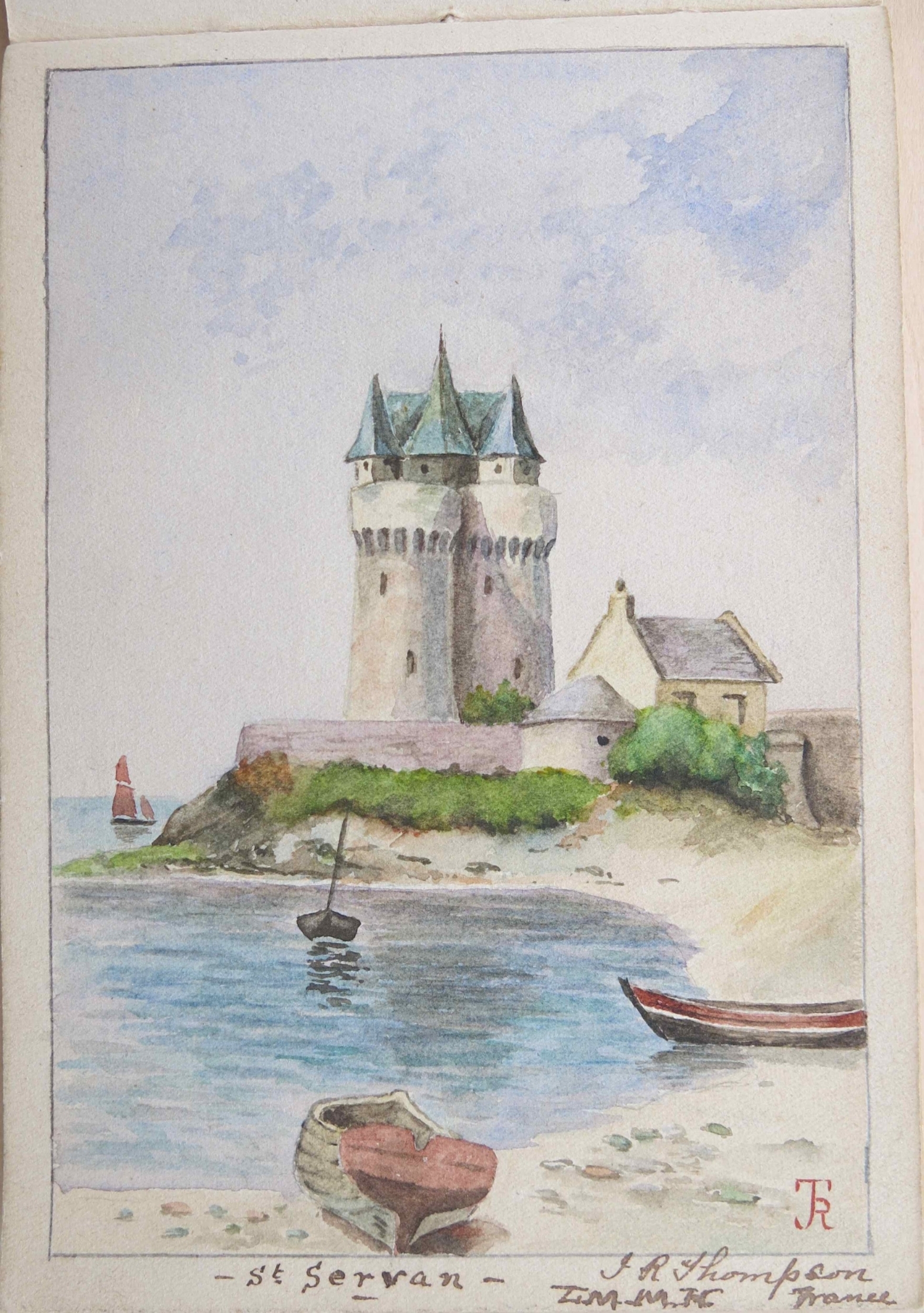

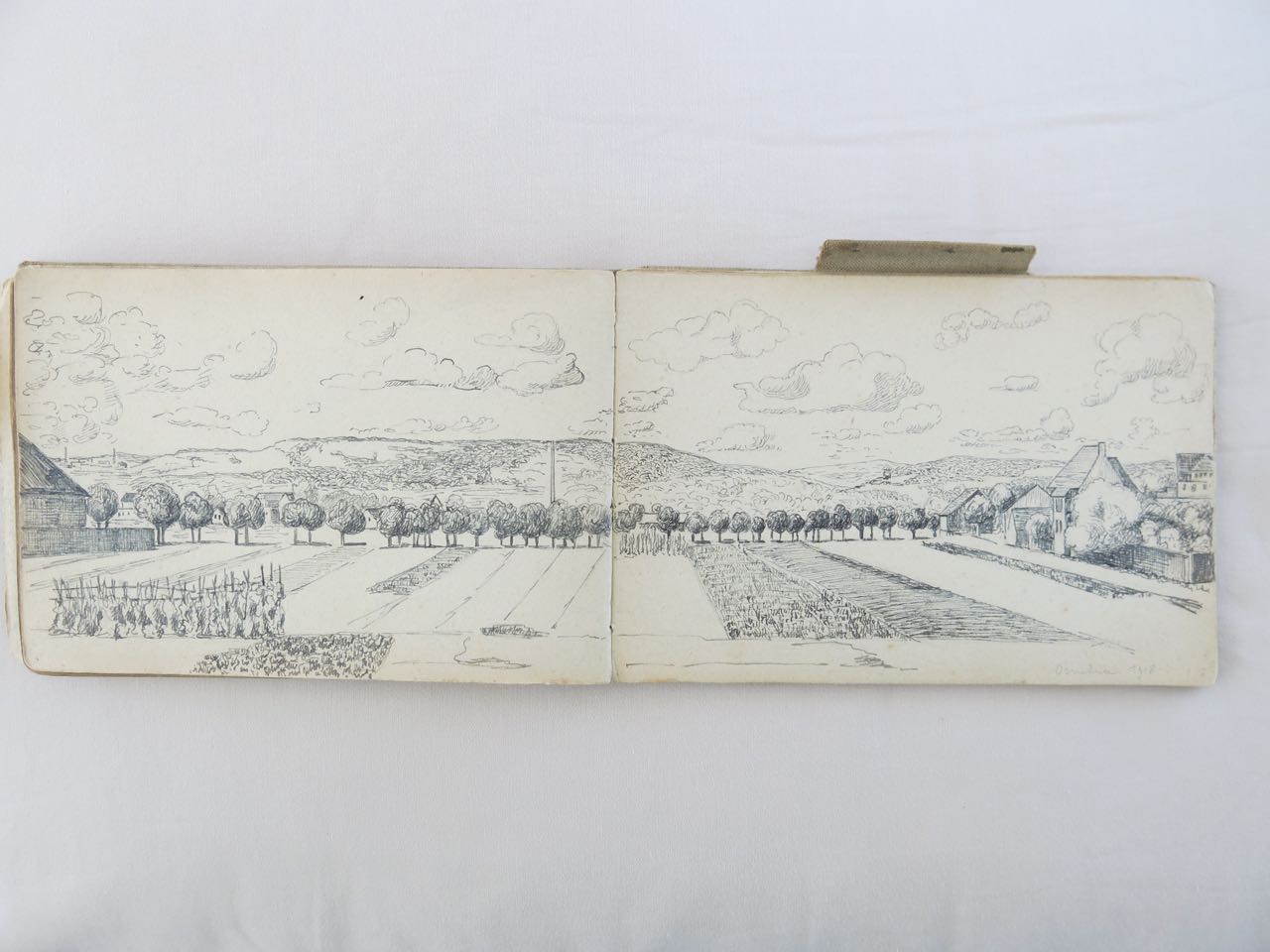

I found it later in sketchbooks from the battlefields, where art from the natural world was therapy for troubled minds. These are from my collection:

- a beautiful watercolour of St Servan, by an orderly responsible for the triage of soldiers wounded at Passchendaele;

- a trusting puppy in a foreign farmhouse, by German officer Kolling;

- a horse resting quietly, by Theo Barker of the Artists Rifles, shortly before he is KIA;

- ‘an evening picture’ and ‘a game of football’ amid the battle scenes of Cutt’s tiny sketchbook;

- the rolling hills beyond the barbed wire in a French officer’s sketchbook;

- a quiet lake by a conscientious objector facing court martial at Abancourt for refusing to load barbed wire.

_____

And now I’ve found a diary by an Australian airman, Joseph Timewell. It’s written in Pitman’s shorthand, and after months of learning from 1913 manuals I’ve managed to translate this: (he’s just back from a reconnaissance flight along the Somme to Abbeville in May 1918):

‘In the evening Jack Dalzell and I went for a stroll in some woods just opposite the drome. Twas a glorious night and I was never in prettier woods. Twas just like a fairytale. Everything was such a beautiful green. The wildflowers were beautiful. Among them were daisies, buttercups, forget-me-nots, polyanthus, bluebells, wild strawberries and anemones and others that I did not know the names of. We strolled about for two hours and twas delightful…'

A few pages later, he describes the scene as a plane crashes nearby. The pilot crawls from the wreckage, his uniform soaked in fuel. The plane bursts into flames, catching the pilot as he tries to escape - and my heart breaks a little. I can read no further.

_____

The website is a work in progress. What I hope to show is the courage of soldiers from both sides, who clung to their values and kept their sense of humanity, even in the midst of a most terrible war.

PREFACE

I am a collector.

Over the past few years I’ve collected true stories from my own family history - rich with smugglers and convicts and the Poor Houses of Kent. There were bigamists and elopements, and scandalous ‘living in sin’. Even the respectable side of the family had rumours of sheepstealing in the highlands of Scotland.

It was a fascinating trail - and I learnt a lot of social history. I was eager for more.

I started collecting coins. I collected tokens because they reflected issues of the times - but they were not personal. I liked engraved coins - ‘Thankyou Nurse from Mr W.D.Ness’ on a silver shilling was interesting, but the story was at best hypothetical.

And then I found collector’s gold - the ‘leaden hearts’ that convicts left for loved ones. These stories were rich in history and intensely personal.

I read Convict Love Tokens edited by Michele Field and Timothy Millett and bought a signed first edition of Sim Comfort’s Forget Me Not.

I was hooked. I hunted with a passion, setting the alarm for the early hours of the morning to bid in the last seconds of eBay auctions. I won the ones I really wanted. And I found the stories behind the coins.

_____

Intriguing pieces started to show up in my searches.

‘Engraved coins’ threw up items under a heading of ‘trench art’. I’d stumbled upon a new lot of coins that told a story.

I bought Trench Art by Nicholas J. Saunders and Trench Art - An Illustrated History by Jane A. Kimball to understand what it was all about. These books describe trench art comprehensively and I make no attempt to cover the same ground.

My focus is on personal pieces where the owner has made or claimed it for his own use and marked it with his ID. My collection consists of personal pieces with rudimentary ID – my challenge was to find the personal story.

CHAPTER 1 PERSONAL TRENCH ART

Talismans and touchstones

The pieces in my collection are not souvenirs or gifts for loved ones at home. They are small personal items to be carried in a pocket or a kitbag.

They are containers for snuff, vesta cases and matchbox holders, inkwells and paper knives and candleholders. They are items to be handled and used, talismans to be touched, as close to hand as a cigarette.

They are not always functional. Some are simple crucifixes - touchstones in the face of trauma.

They all belonged to Non Commissioned Officers and Other Ranks. These were the ones who faced the long tense hours in the trenches before an attack, waiting for orders, all too aware of the trauma that lay ahead. There was often a need for silence, and even a small light could betray their position to the enemy. In the midst of an army, they were alone with their fears and thoughts.

The pieces are tactile, and they are personal. Each one is identified with name and serial number, often with regimental insignia - not necessarily of the person who made it, but the person who claimed it as his own and carved his name and number on it.

Many pieces are unique. The music pieces in particular are highly original in their design. Perhaps they were a claim on individuality - nearly everything else was army issue. Everyone looked the same, dressed the same and carried the same kit - but some pockets held a small piece that was different, marked with name and number because it was important.

Art in the face of trauma

I was talking to my son-in-law at a family gathering recently. He’s a professional working in the area of mental health. He listened as I described my passion for this project. ‘You might like to look at the research that’s being done on the role of art in trauma therapy. It’s showing that creating something in the face of trauma can help a person - it gives a reason to face the next day. And it leaves something tangible to show that it happened.’

I knew about the handicrafts that were encouraged in convalescent wards during WWI. That’s where occupational therapy started as a profession.

On the battlefield, perhaps it was an intuitive response to the horrors of war - a way to focus on a world outside the war.

I thought of the pieces in my collection. They’re not about war. They are about music, and religion, and love - and letters home.

They are often worn as a fob - to be held and used, clung to metaphorically and physically. That is what moves me as I hold them now. They are tactile, smooth and worn, much handled - like worry beads or a rosary between the fingers.

As I hold these items, I think of the soldiers who held them. I need to tell their stories.

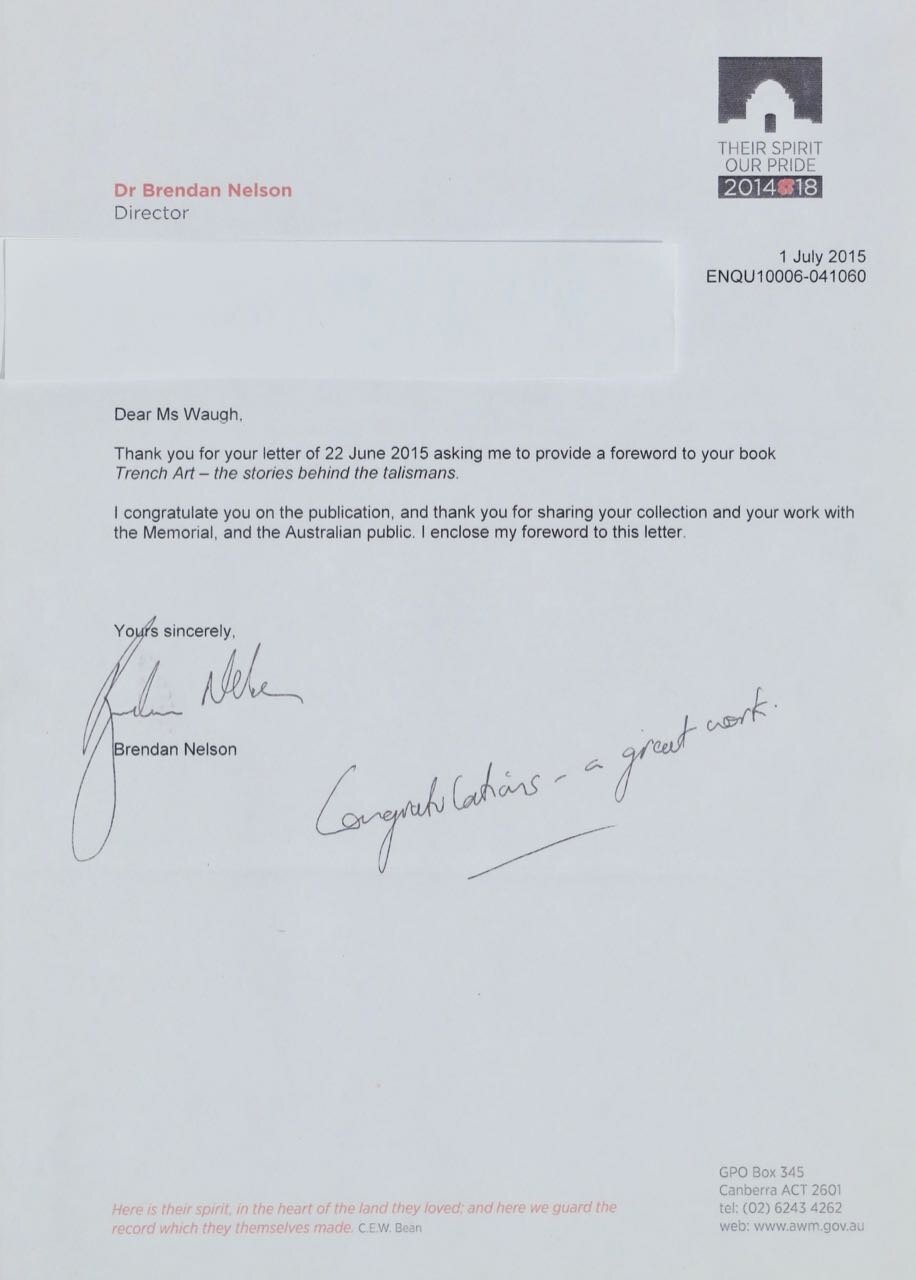

Foreword

by

Dr Brendan Nelson

Director, Australian War Memorial

Australian institutions such as the Australian War Memorial have a proud history in preserving Australia's heritage. However, individuals have a vital role in this, too. Many people, including families, groups, and private collectors, are keen to ensure the survival of the objects that reveal our past. No one deserves to be remembered more than those who served our nation in war and who, too often, gave their lives.

Judy Waugh is a dedicated collector of wartime trench art. Her interest is concentrated on those small personal items which she calls "talismans in times of trauma", made by soldiers from the limited available materials during wartime. The selection of objects she has assembled is remarkable, and all the more important because she has researched the details of the soldier involved; the so-called, "man behind the object". Many of the soldiers whose stories she reveals are Australians, but there are others, too. The power of the objects is in the story of the men and women behind them. It is this especially which makes the book so compelling.

Even though a century has passed since the First World War began, the stories of individual soldiers can still be brought to life by examining the existent records. So much of this information has become available online. I am proud that the Australian War Memorial has been in the forefront of making its records digitally available.

Sharing is an important part of preservation. Judy Waugh's book is fascinating for its fine photographs of small objects. The craftsmanship ranges widely (though many are fine works), but each object displays immense ingenuity and, through Judy Waugh's research, tells stories of service and sacrifice.

I am very happy to encourage this work and thank Judy for sharing her collection with us and the nation.

_______

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I owe this collection to Steve, an old soldier I never met, who wishes to remain anonymous. Without his support this collection would not exist.

Steve understood the nature of the collection and acknowledged the passion behind my search for the stories. He dragged suitcases from the attic and sorted through his own collection, offering me unique pieces that had names and service numbers. He then scouted for more, searching through militaria fairs and auctions from deceased estates, bargaining on my behalf.

His support for the book was wonderful and unwavering, his enthusiasm carrying me through the darker moments of committing to print. To Steve I offer a heartfelt thankyou for a project that has intrigued me for the past few years.

I thank the archivists and family historians who answered my queries with interest and encouragement, and who gave me permission to publish their images and information.

In particular, I thank Anita Roe for allowing me to quote the diary of her great-uncle Frank le Brun for the days leading up to his landing at Gallipoli. And I thank Shane Lenfestey Langlois for permission to use his grandfather's account of the 1919 action in the Caucuses - similar to the official accounts but told from a personal perspective. I understand these are precious documents, and appreciate being allowed to quote from them.

I thank Christopher Dawkins from Felsted School, Alice Clanachan from the Art Gallery of South Australia, Jane Harding from Noosaville Library, and Helen Armitage from Conwy Town Council for time they spent on my behalf, and Sally Mullins, Geoff Allan, Joe Eastwood, Sally Randall, David Cornforth and Rob Belk from family history societies for friendly assistance with my research.

I thank the National Archives of Australia, the Australian War Memorial, and Archives New Zealand for their kind permission to publish, and as in the case of those mentioned above, for adding their personal encouragement and best wishes for the book.

I thank Tony Dwyer for photographing the collection in a way that allows others to see the unique beauty of the handcrafted pieces.

Finally, thanks to my family and friends, who not only encouraged and supported me, but edited with accuracy and gave me honest feedback, thereby saving me from infelicities and anachronisms.

My focus is on finding the story. These are personal pieces. The challenge is to find the personal story - to solve the puzzle, reconcile the anomalies, reject the false trails, and be confident that I’ve not only found the story, I’ve found the right story.

To do that I need more than a name. Even a name and regiment is often not enough.

I started to be more selective in my bids on eBay. I noticed that several ‘must have’ pieces- including the banjo - were from the same seller in the UK. I’ll call him Steve to protect his identity; he had a suitcase of trench art stolen years ago and has been cautious since.

I emailed Steve when the banjo arrived. It was perfect - functional, beautiful, and personal, and I thanked him for it. I learnt that Steve was selling off part of his collection to fund a different type of militaria. We talked about Australia, and the weather, and our collections.

Thanks Judy, have a lovely day, I had a look at your location, it looks beautiful - how very fortunate, we are having terrible weather here . . .

I explained my passion for this collection in my reply.

Subject: Re: Interesting collections

My sympathies on your weather, Steve. My Dad came out to Australia from Scotland alone when he was 19. He loved this part of the world. He used to say ‘Well, Jude, I've seen a lot of the world - but I reckon this is about as good as it gets.....'

I married a man from Scotland and we travelled the world on slow boats and small cars with kids and tents - and I think my Dad was right.

One of the motivations for my trench art collection is to show my grandchildren how lucky we are to live in a beautiful peaceful country - and that life wasn't always sunshine and beaches.

I'm trying to tell it through stories of real people - not through the horrors of war but through the ways they marked their individual presence in the battlefields.

They were people with names and families and loved ones, not just battalions and regiments.....who lit cigarettes and talked to their mates and carved their names on pieces of metal...

Along the way I am learning so much myself.

Thankyoufor helping me in my small act of discovery.

Cheers

Judy

Steve has been collecting militaria for many years. He’d always meant to do the research - but of course it was much harder years ago, before records were digitised and put online. Now he has moved on to a different focus in a different war.

In offering me the personalised trench art he could fund his new collection. He parted with unique items knowing that I would do the research and respect the stories. I felt privileged to be trusted with such beautiful pieces. I am reminded of Timothy Millett’s story of how he came by his collection of convict coins - Steve is my Mr Vorley.[i]

[i] Millett: 6

Tony Dwyer spent many hours photographing the collection, showing the inherent beauty of the design and the ingenuity of construction.

The result is a superb series of photographs.

Tony was also responsible for the graphic design and layout of the book, converting my Word documents into print-ready files.

Tony Dwyer runs his business ADFX Graphic Design from Brisbane, Australia.

G LOWRIE 9890 ROYAL HIGHLANDERS - BLACK WATCH

I found George Lowrie on the Edinburgh University Roll of Honour with a photo of him as a young man.

I went looking for a life of privilege. The story I found was very different. It was a story of factory workers doing the best for their child - only to see him lost on the battlefields of France.

W K SCOTT 40379 NZR

William Kenneth Scott, born in New Zealand, sailed halfway round the world to fight for the land of his parents. He fought for King and country, and proclaimed it on his drum.

ARTISTS REGIMENT 1st 28th KHP 766615

I was deeply moved by holding this. It is smooth and tactile, much handled and worn. It belonged to Kenneth Herbert Pearson - a quiet lad 'of infinite good temper' who left school to join the Artists Regiment in 1917. As part of the Great Advance, he went over the top four times in five days. . .

R ARNOLD 2362 RWKENT

It was the day he died - the first day of the Battle of the Somme - that told the story of Richard Thomas Arnold. He was one of so many.

R W BELL 125333 RFA

Richard Whitling Bell remained a mystery until I found a Will that led to Crathorne. There he went from virtual anonymity to a brush with one of the most famous families in England - that of Sir Isaac Lowthian Bell and his granddaughter Gertrude Bell.

A A MORGAN 21382

Albert Arthur Morgan - a Shropshire lad - came from a long line of farm labourers. The monogrammed silver cigarette case, the fine swagger stick and the studio portrait suggest he was loved and admired before he left for the Somme.

J GREGORY 2745

There were signs of overcrowding and hardship in James Gregory's background. There were also signs of love - a photo of a beautiful young woman hidden in a secret locket in the heart of the ukelele.

E HOGBEN 22900

This piece gave me goosebumps. It once belonged to someone on my family tree - Edward George Hogben from Bonnington Kent.

It came to me through the hands of strangers, across a century of time and half a world of distance.

Among the items sent to his mother after his death were 14 photos. Perhaps one day they will surface, like the mandolin, miraculously.

H G GINGER 44 1652

Herbert Ginger was just a teenager when he emigrated to Australia alone. He was still a teenager when he returned to fight for his country three years later. He was 20 when he died on the Somme.

W FISK RAMC 20294

William Fisk survived three long years on the battlefields of the Somme and was recognised for his courage under fire. He found wartime romance and married, only to be killed in action a few weeks later.

W SCOTT 40379 NZR

William Scott made his Will shortly after his training at the Lewis Machine Gun School. He was wounded in action at Doullens two weeks later and died at the Casualty Clearing Station. He was 23.

W WILKINSON ALH 751

It was possibly innocence that led Wilfred Wilkinson to months of ostracism and isolation in a foreign land far from home.

V DENTON 618 ALH

When young Victor Denton was killed at Gallipoli in 1915, the small farming community at Nobby were shocked at the death of one of their own. They raised funds to build the first known WW1 memorial in Queensland.

E H LADD 5094

I found Edward Ladd in the National Archives of Australia. As I read through his file the story unfolded layer upon layer.

It is the story of a young man who fought at Gallipoli and survived only to die on the Somme. It is a story of mateship and courage under fire.

N KELLY 2657

Nathaniel Kelly was the perfect candidate for the Tunnelling Corps - a young fit miner from the coalfields of Ipswich west of Brisbane. He was 23 when he helped blow up Hill 60, an historic event that was made into a movie 100 years later.

H HAMMOND 771 ALH

Henry Hammond fought with the Bushmen Contingent in the Boer War and survived. At the outbreak of WW1 he was older, married, and living in Adelaide - an unlikely candidate for the Australian Light Horse. So he reinvented himself, moving to Blackall in Outback Queensland and enlisting as a single drover, aged 30.

He was killed at Gallipoli a few months later, aged 38.

H G GINGER 44 1652

The inventory of effects sent to Herbert Ginger's next of kin included an unlikely 'cigarette holder'. There is an unusual cylinder attached to the cello - perhaps designed to stand firmly in the mud to hold a lit cigarette.

W F HILLMAN 3060 1916

William Frank Hillman looked like trouble from the start. He already had a bullet wound to his leg when he enlisted in Brisbane as a 20 year old.

J ADAMS ICC 571 1916

These simple clues led to the story of James Alexander Adams. The NZ Archives gave everything - embarkation, Egypt, Gallipoli, where and when he was wounded, hospitals, the Imperial Camel Corps and finally his death in Egypt on the boat that was to take him home.

J H SINCLAIR 2014

The file on James Haining Sinclair shows how much importance was attached to personal items sent to next of kin, and the pain it caused when they went missing.

T A DONALD 6952 16th AUSTRALIA

Years after his death, Thomas Donald's mother desperately wanted to know where her son was buried. The official reply was brutal in its formality: Failing the discovery and identification of the actual remains . . .

H L ROOTES 2989

I think it is very hard after three years active service, to only get one old razor strop, all mouldy and covered in clay . . .

Thus wrote Henry Rootes' mother after she opened a parcel containing the wrong effects.

In the first place he never had a razor strop . . .

I take it as an insult, to the lad who fell for King and country, and also to me his broken hearted mother.

T H O ADAMS 7919 RAF

W PLATT 3411

William Platt survived the Boer War. His locket, made from date-significant pennies, is similar in style to that of Henry Hammond, the Australian serving with the Bushmen Corps. Like Hammond, he may have been subsequently killed in WW1.

O HOGG RN 1916 'WINNIE'

Owen Hogg's records presented a conundrum - how did an Able Seaman who 'died at sea' become buried in the Etaples Military Cemetery?

T LONG 1916

Thomas Long was caught up in one of the most devastating and brutal theatres of war. Perhaps this small cameo, with its date 1911, was his secret talisman - the memory of a girl he loved in 1911 when he was 20 years old and his country was at peace.

H HAMMOND 771 ALH

Henry Hammond said he was single when he enlisted in WW1. Helen Scott Hammond said he was married. Records show he was, in 1910.

And when he died at Gallipoli, he had a locket with a small halfpenny with their initials either side of a stippled crucifix.

J GREGORY 2745

Perhaps the beautiful girl in Gregory's secret locket was a Red Cross nurse - her collar suggests that she was.

E GARRETT 241437

Ten days after Elijah Garrett entered the war in France, he wrote a Will in his Army Book leaving everything to his mother.

V BARNES OB RGT

It was sunstroke and dysentery that caused the death of Valentine Barnes in a foreign land far from home, a few weeks before the end of the war.

G SMITH 1316 ROYAL HORSE GUARDS

The symbolism on these two pieces is simple and strong: the Royal Horse Guards, Christ on the Cross, the King on the ring, and love - Godfrey Smith was married. Loyalty, love, faith, honour and duty - all in two small items that fit in the palm of a hand.

T H O ADAMS 7919 RAF

The kite balloons of WW1 were huge and cumbersome. It was Thomas Adams' job to keep them airborne.

R SAWYER 1905 H R

A utilitarian piece of silver has been transformed into a personal talisman for faith and love. Ralph Sawyer died at Gallipoli two days after he landed.

J GOUGH G H

Jim Gough entered the war in France in 1915. He was wounded near Etaples in 1917.

Jim Gough knew he might not survive. He wrote his Will eight days before he died of his wounds.

L CASTLE 345369

This piece is rich with symbolism. The natural shape of the wood suggests the Madonna. There are traces of wax. The association of candles with churches and prayers adds to my emotional response. This is a beautiful piece - a religious work of art from found objects.

W C 203255

Those within the Catholic church recognise the bone container as a pyx, designed to carry communion wafers, and the box as a container for sacramental oils.

William Cortez - brought up in the Homes for Little Boys in Kent - may well have been qualified to administer last rites to wounded soldiers on the battlefield.

H L ROOTES 2989

I think it is very hard after three years active service, to only get one old razor strop, all mouldy and covered in clay . . .

Thus wrote Henry Rootes' mother after she opened a parcel containing the wrong effects, after his death on the Somme.

W FISK RAMC 20294

William Fisk survived three long years on the battlefields of the Somme and was recognised for his courage under fire. He found wartime romance and married, only to be killed in action a few weeks later.

H T COBB A S H 303106

This is one of the most beautiful pieces in the collection. The design is complex, but it sits easily in the palm of the hand, pleasantly tactile like most of the pieces. Perhaps for Henry Cobb it was something bright and golden in an otherwise grey and uniform world.

B C BEAVER 62365

Bernard Beaver was a promising violinist. He was the last of his line. He was 23 when he was killed in action at Amiens, a few months before the end of the war.

J GRAINGER E Y RT 15048

James Grainger wrote his Will on the way to Gallipoli in 1915. He survived, but was killed in action near Ypres two years later.

RF A PELHAM A 24711

Arthur Pelham had a special reason to write letters home - he was newly wed when he enlisted.

S W BREWER 1807 THE BUFFS

Sidney Brewer was 22 and a long way from home when he died of illness in the awful heat of Mesopotamia.

J ADAMS ICC 571 1916

Such small clues - such an explosion of stories, with the ghost of Lawrence of Arabia in the background.

W PLATT 3411

This is the second item from William Platt in the Boer War - a small retractable bone knife in the shape of a Victorian lady. Beautifully made.

H L ROOTES 2989

L CASTLE 345369

A G CHENERY 6135

Arthur Chenery survived many historic battles only to be killed in action the day before the Great War finally ended.

HMS CONTEST T COLLINGS RN

Thomas Collings was a slightly built, fresh-faced youth of 18 when he joined the Navy. He was still growing, his 5 foot 4 inches at enlistment increasing to 5 foot 4 1/4 inches when he was measured six months later.

J GEDDIE 39484

John Geddie should never have been in India in 1918. He'd been discharged as medically unfit years before.

W F HILLMAN 3060 1916

William Hillman not only lost his rifle, bayonet, scabbard and ammunition at the Serapeum in Egypt - he also lost his clothing.

R M ARMOUR 241124

Robert Armour served three years in three different theatres of war - Gallipoli, Palestine and the Somme - only to be killed in action a month before the Armistice.

490137 H BASS LOVE F RF

The inscription remains enigmatic. My reading of it has two families united by marriage. Three young men dead. One shared gravestone.

P E KING DR 10

It was all about securing the oil lines.

When Philip Embrey King was killed at Batoum nine months after the Armistice, I was mystified. The answer came from the diary of Edmund Lenfesty who wrote One of the main objects of the British was to guard the oil wells, all along the railway line from Baku to Batoum . . .

T WEST 69457 XXIII

W WILLIAMS 2646

William Williams left school by the time he was 12 and followed his father down the mines. By 1911 both William and his father were working as hewers, digging coal from the face of the rock deep in the pits.

1916 F MICKLE MACHINE GUN CORPS 70569

Frederick Mickle was the only child of working class parents. He had piano lessons and performed well at Trinity College exams. He won prizes for shorthand and was mentioned in the Dover Express.

So many simple hopes and dreams were lost in the mud of Flanders.

H HALE

Gunner Hale served with the Royal Artillery in Crimea during the Siege of Sebastopol.

He died at Karani in June 1855 at the age of 20.

BATEMAN 40908

Gilbert Bateman came from a long line of factory workers in the West Riding of Yorkshire. As a child, he was raised by his widowed mother, and worked as a doffer in the woollen mills. The doffers were usually the sons of poor people, and were small and skinny. . . As a rule they would go barefoot except at the coldest time of the year (Wiki).

V DENTON 618 ALH

The tragedy of Denton's death at Gallipoli was exacerbated by conflicting telegrams sent to his widower father, who later sought clarification through the Australian Parliament. It was no-ones fault. The complications of maintaining communication between the battleground of Gallipoli, the hospital ships waiting offshore, the hospitals at Alexandria, and families back in Australia were enormous.

T KIDD 291674 1917

Perhaps Thomas Kidd, the son of a joiner and cartwright, found comfort in carving. He converted part of a rifle butt into a benign tobacco box and carved his name into the wood.

Q W R

F W LONGMAN 1916

Frank Longman had already willingly served in the Territorial Forces, but that did not stop him from being conscripted in 1916.

V BARNES OB RGT

Pte A JOHNSON 302300 M.T.A.S.C. BAGHDAD 1917.18

Alfred Johnson survived the war. At demobilisation in 1920, the Medical Board assessed his condition.

Complains has had two attacks of malaria in last three months - shivering, sweats, headaches. Last attack three weeks since (very severe). Weakness for two days.

W BOOTH RFC 33605

William Booth was one of the first to enlist. He served in France with the RFC.

He arrived in Mesopotamia in August 1917.

63 Squadron arrived in Basra on 13th August 1917 into the baking heat of well over 100 degrees Fahreinheit and promptly went down with heat stroke. Only six out of 30 officers were left standing and only 70 men out of 200.(Great War Forum).

William Booth died 11 days later.

W PELHAM CE 8349 ROYAL SUSSEX FRANCE 1914-15 MESOPOTAMIA 1916-

The story of William Pelham has a happy ending, all the more amazing because it spanned the war from start to finish and covered action in two of the most tragic theatres of war.

J McBLAIN 12703 RAF 1916-17-18 MESOPOTAMIA

James McBlain remained a mystery until his RAF service record became available online, with the address of his father as next of kin. A search revealed James had lived at that address since he was a child of 4, and his story fell into place.

KAZEMIAN 1917-18 No. 579. MTPC.

I asked for help with the translation and Ibrahim Abdelsaheb kindly replied.

interesting search. I am from kazumain, and can translate what is written in arabic.

on top is says (no God but Allah...and Mohamed is his messenger ).

also on lower right side..it says Bagdad.

JOHN BRUNT 8760

John Blunt served in Mesopotamia. More than 12,000 men died of sickness during the campaign - but John Blunt didn't die of sickness. The covering note to his Will shows that he was killed accidentally at Bangalore while on active service.

Cpl G.H. FORD 38747 M.G.C (H.B) France 1917

M.G.C (H.B) is the Machine Gun Corps (Heavy Branch). The Heavy Branch separated from the MGC to become the Tank Corps in 1917.

E J DICKS 235622

G SMITH 1316 ROYAL HORSE GUARDS

A A MORGAN 21382

H HAMMOND 771 ALH

W C 203255

L CASTLE 345369

I bought this sketchbook on ebay recently. I started a search for H. Ogle - and found to my delight that there was a book written about him and his sketches: THE FATEFUL BATTLE LINE - The Great War journals and sketches of Captain Henry Ogle, MC.

It's the same Henry Ogle. His journals mention his time at the Liverpool Merchants Mobile Hospital at Etaples, the setting for this sketchbook.

I learnt that he was born in Australia in 1890 but was sent to England as a 4 year old after his father died, to be raised by an uncle. He enlisted not long after war was declared.

His journals show him as a sensitive, warm and likeable young man who made friends easily. There is no anger or bitterness in his journals. He saw his German counterparts as brave men doing their job. He himself was brave, awarded the Military Cross. One of his few complaints about the war was that when he received his Military Cross it had no name on it. 'I found that the Cross was not engraved as I expected it to be, with name, rank and regiment. There was nothing on it to show I had any right to it. All my other medals are engraved. And so, like a proper soldier, I end this narrative with a grouse.'

. . . . .

His journals tell the story of his time at the hospital.

He didn't want to be there. He felt a fraud. He'd injured his knee during officer training in England, and exacerbated the injury on his way to Passchendaele. The swelling was such that he couldn't get his breeches over the knee and he was sent to the Liverpool Merchants Mobile Hospital (LMMH) at Etaples for treatment.

It was a hard time for him, being among the genuine war-wounded. 'While I was recovering . . . there was being fought the slimiest and bloodiest battle in the history of the British Army. I escaped it but, with first hand knowledge . . . could form some picture in my mind of Passchendaele.'

Henry Ogle carried sketchbooks throughout the war, with a miniature paintbox. This one has the name C.Lloyd handwritten on the cover. Sarah Lloyd was a nursing sister at the LMMH according to the British Red Cross Register of Overseas Volunteers, and was the subject of one of his sketches.

Henry Ogle struggled during his time at the hospital - so many around him were deeply traumatised. The worst of the casualties were beyond communication. Even those with lesser wounds were unwilling to talk about it.

'. . . many wore an air of bogus devil-may-care which deceived nobody.'

'We had on our nursing staff some VADs who helped to keep us cheerful. It was a strange, unreal, unsatisfactory, even demoralising, life during the convalescent stage.'

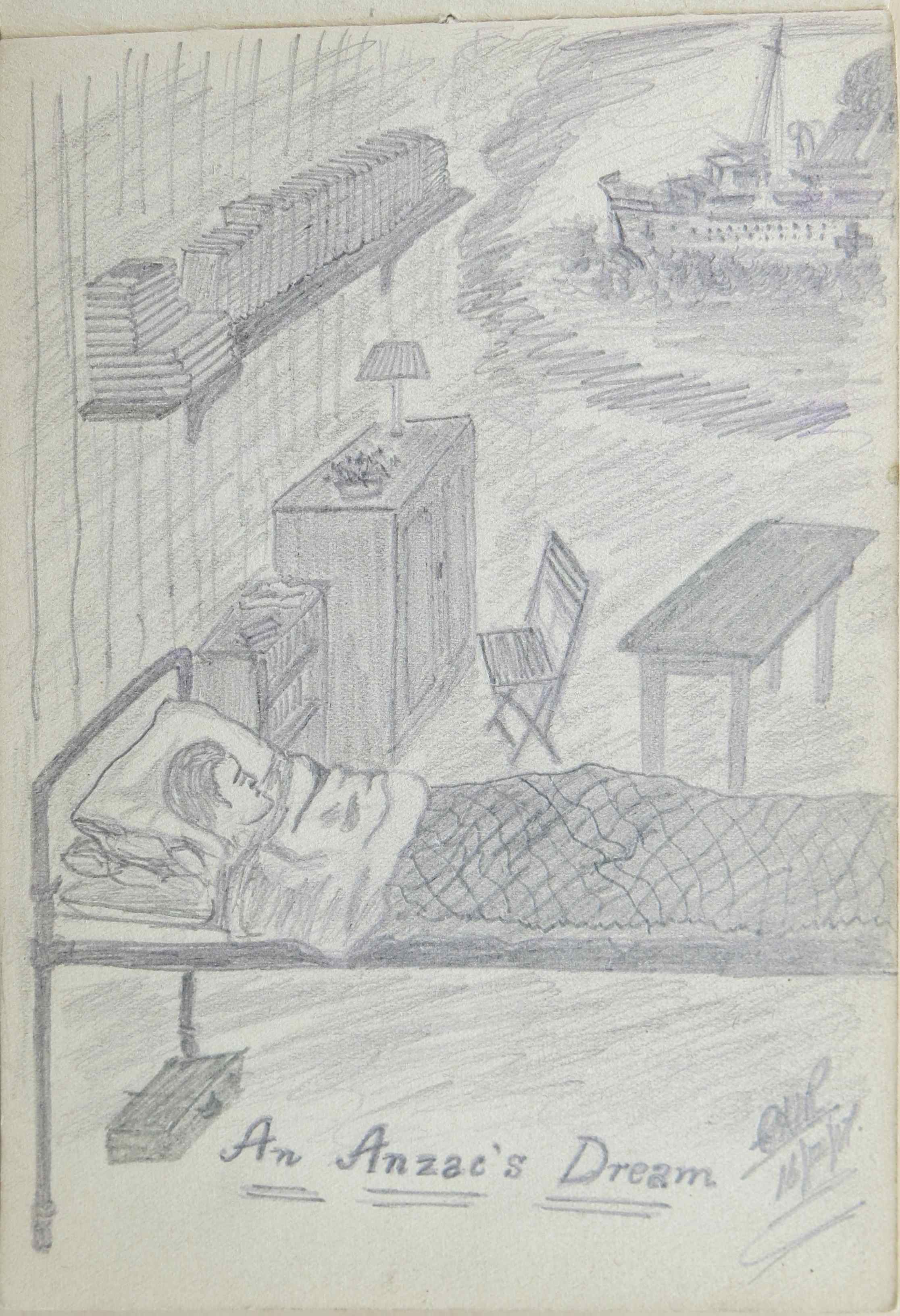

Henry Ogle started the sketchbook with this humorous, gentle sketch of his own, and set the tone for the rest of the offerings. His VADs were easy to find - Sister Lilian Hamilton Taylor with her 3 seconds bed making stunt, Sisters Sarah Lloyd and Phyllis or Martha Wilson at the Davits, and hospital assistant Dorothy Mary Hughes taking 'some' pulse. All were Red Cross volunteers from Liverpool.

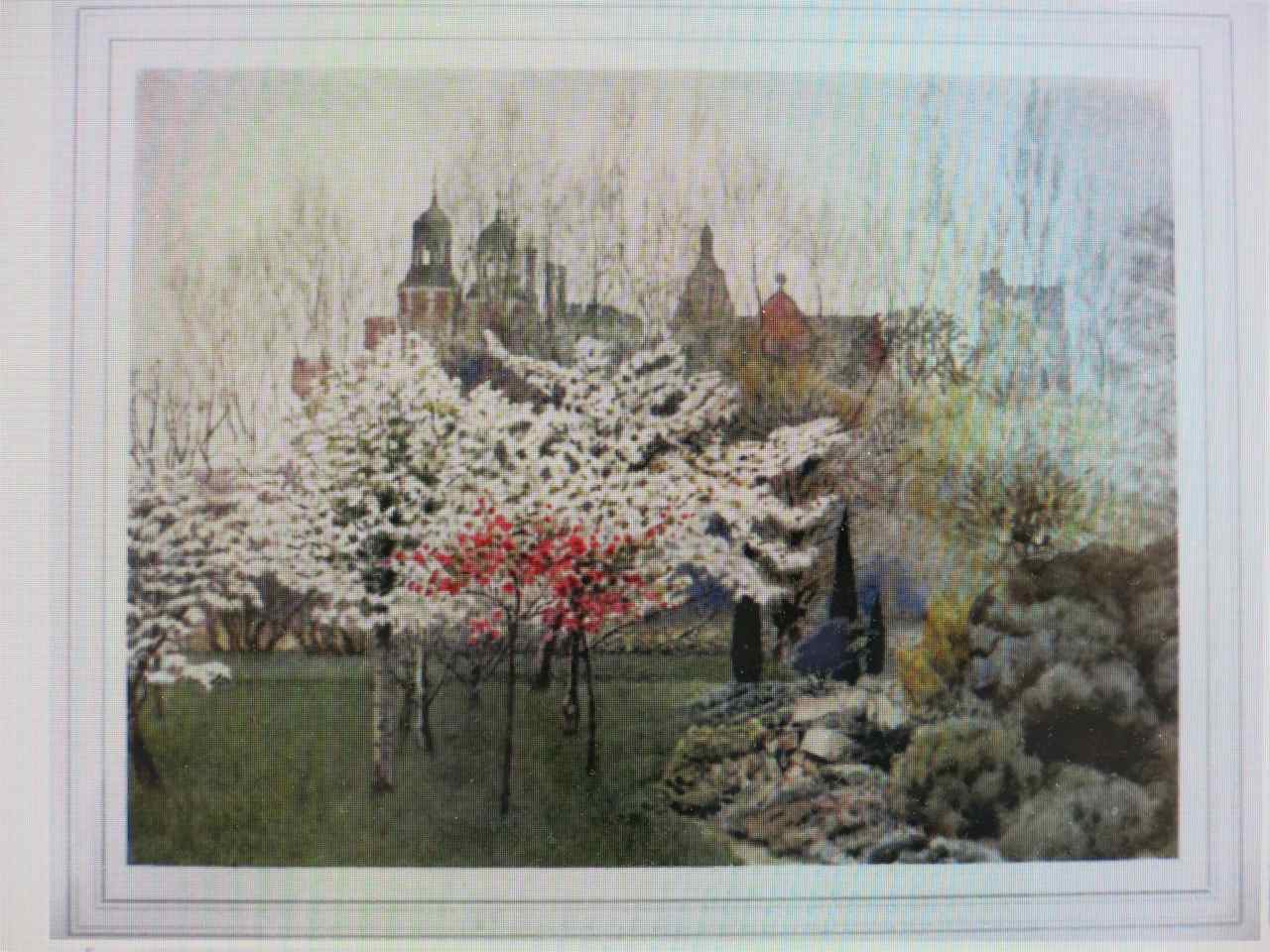

This beautiful watercolour comes from Henry Ogle's sketchbook. It wasn't his sketch.

This was painted by an orderly at the military hospital at Etaples, John Thompson. As an orderly, Thompson would have seen the most horrific of injuries after Passchendaele.

This was his therapy - to become lost in the calm peacefulness of a beautiful day, and to share it with others.

Henry Ogle also sketched this area. The rough sketch below is from The Fatal Battle Line.

Henry Ogle sketched this scene during his convalescence at the LMMH at Etaples. In his journal he writes

'The seaside resort of Paris Plage was only a tram ride away and one afternoon I thought of a possible sketch on the beach. The tide was out, far enough to be able to visit the wreck of a cargo steamer which had been torpedoed in 1916. It had been beached but was broken in two parts which became widely separated in a gale.

I managed to get a very slight sketch of it before the tide made me leave the beach. At last I read my name on the posting list and left Etaples without regret.'

This is a particularly moving sketch from Henry Ogle's sketchbook. The soldier is in the military hospital in Etaples, along with many other desperately wounded men caught up in the battle at Passchendaele in 1917.

He dreams he is tucked up in bed on the other side of the world, safe in his old bedroom.

He chose to sketch his dream rather than the awful reality around him.

Captain Frederick Richardson was born in England and had previously served with the Gordon Highlanders. He enlisted in the Canadian Infantry in 1915 and gave his next of kin as his wife Emma. His big-hearted welcome was genuine. A search on the Canadian address showed a house for sale in 2001. It was constructed between 1915 and 1918 and the original owner was Frederick Richardson.

I found Francis Robert Boyd Haward on the website of The Society of Old Framlinghamians.

Francis Haward had a distinguished service history.

He served in the Royal Norfolk Regiment during WW1 and was wounded twice, according to that website. He served again in WW2 in the Home Guard and was eventually awarded an OBE. Saved life from drowning. Was a Fellow of the Royal Institute of British Architects.

Francis Haward was wounded twice in WW1. Perhaps this sketch is a reference to his repeat visits to the hospital at Etaples. Ward C was possibly for those driven mad by the horrors of war - Haward sees himself still going back there in 1947, chatting up the nurse who by now is bent and decrepit.

This is enigmatic. The tone of the sketchbook is respectful rather than suggestive.

Perhaps the only way to get the nurse to examine him was to pull the stitches out?

The signature is too indecipherable to trace, other than that he was in the Machine Gun Corps.

This is another sketch by Francis Robert Boyd Haward. It's suggestive, but like the others reasonably respectful.

These look like the work of Henry Ogle - practice sketches. There are similar sketches in THE FATEFUL BATTLE LINE.

This came from an old scrapbook kept by Launcelot A Luxmoore over many years. Most of the contents were newspaper clippings. This sketch was carefully cut from the page, still on its backing paper, because of its WW1 interest.

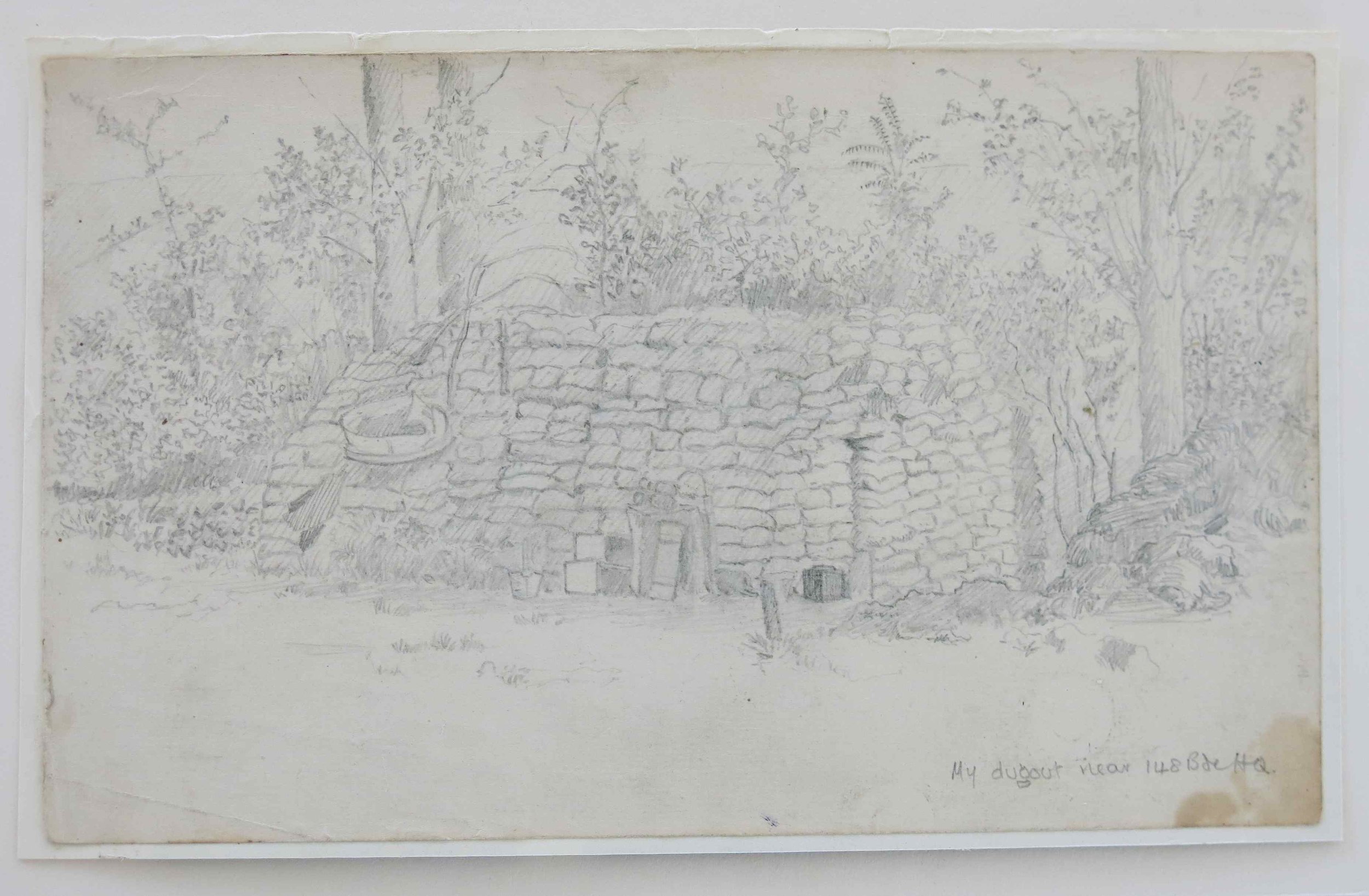

It's a pencil sketch approx 7 inches by 4.5 inches.

My dugout near 148 Bde HQ is handwritten on the bottom right.

Like the rest of my collection, this is not about war.

Luxmoore's dugout is a beautiful place, a sanctuary rather than a place of grim reality.

LA Luxmoore did face the realities of war. The scrapbook shows he served first as a Captain then as a Major with C Battery, 149 Brigade RFA. 149 Brigade travelled to the Western Front in the autumn of 1916 and remained there till the end of the war, spending much of that time on the Somme.

I am indebted to David Wilkins who took such care with removing the sketch from the scrapbook. David gave a meticulous description of the item and provided significant research on the background.

He also provided the images below.

_ _ _ _ _

The cutting below is pasted to the reverse of the scrapbook page. I include it here to show the recognised importance of the oil lines in Iraq.

The imperative to secure the oil lines in Iraq is central to the story of Philip Embrey King, as told in Trench Art under ‘King’s matchbox cover’.

One of the main objects of the British was to guard the oil wells, all along the railway line from Baku to Batoum, some 500 miles, were four rows of big oil pipes. From Lenfestey Langlois diary, post-war intervention in Russia, quoted with permission in Trench Art.

For this section, I am indebted to the family of LA Luxmoore, who generously agreed to the display of these images, and who shared stories from their family history.

I'm particularly grateful to LA's grandson Fairfax, who drew together stories from the extended family. And to Herry, who passed on my original request.

HE Luxmoore was a Housemaster at Eton for nearly 50 years. During that time he tended the beautiful garden that bears his name.

The plaque at the entrance states

THIS GARDEN WAS BEGUN IN THE YEAR MDCCCXC BY H.E. LUXMOORE.

FOR THIRTY-SIX YEARS HE TENDED IT AND SHARED IT WITH HIS FRIENDS, YOUNG AND OLD . . .

One of those was LA Luxmoore, who was in his House at Eton.

Years later on the Somme, LA Luxmoore made a pencil sketch of his dugout, in a style reminiscent of HE's paintings of the gardens at Eton. This is how he chose to see his dugout - as a safe haven.

Like Henry Ogle, he continued to see the beauty of the world even in the midst of war. He captured it in his sketch, and held on to it. Henry Ogle captured it in his journals as he travelled from one battlefield to the next in France: 'There was a smell of grass where our bus wheels had rolled over a verge; there were garden flowers, farmyard and barn smells and the baking of bread. The village nestled among trees, all in the full, rich green leaf of high summer, and was bright with cottage gardens and orchards.'

They travelled through a world of horror and death, and still found beauty.

LA Luxmoore survived the war and married Connie, the daughter of a housemaster at Eton.

That's Launcelot Luxmoore, third from the left with Connie (seated) at the wedding of their son Arthur in 1935.

This wonderful German sketchbook belonged to Kolling, a Lieutenant in the 22nd (2nd Westphalian) Field Artillery who served on the Western Front in 1915.

I've numbered the sketches and shown them in the order they appear in the book, to preserve continuity of context.

K12. The earliest date is 20 Mar 1915, under the sketch of a burning church. Presumably the earlier sketches refer to the Winter of 1914 - 15.

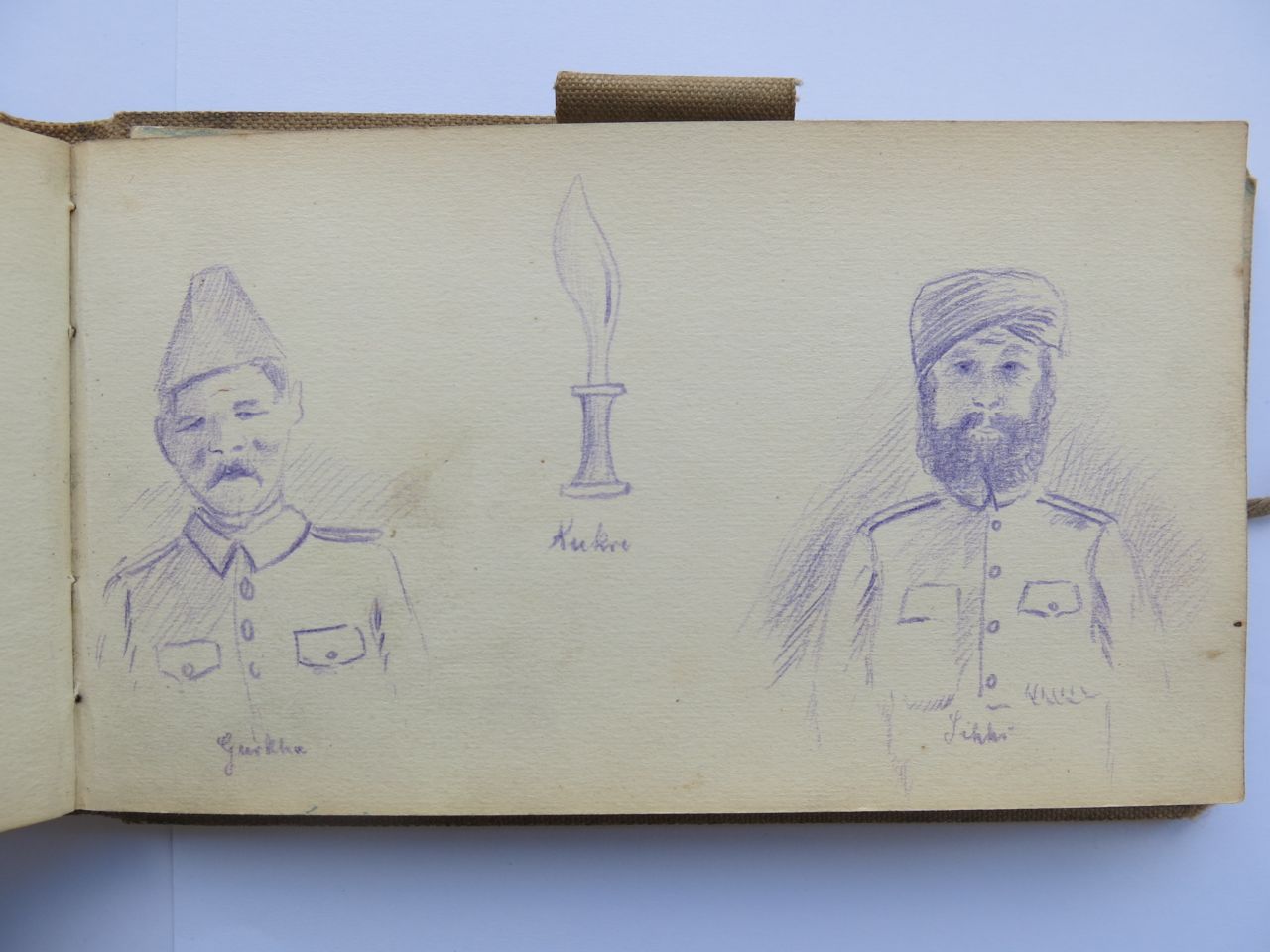

K28. The sketch of Gurkhas possibly follows the Battle of Loos (25 Sep ~ 19 Oct 1915) where many Gurkhas were killed or taken prisoners of war.

The 'dedication' date inside the front cover is 20 October 1915.

K15. The 'dream' sequence is dated 26 Nov 1915.

K17 is dated 20 Dec 1915.

K23. The celebratory bottle of wine near the end of the sketchbook is dated 6 January 1916.

Inside the dugout. Kolling's gun is in the background, on the shelf. His shaving mirror is centre stage. His coffee jug and personal items are neatly lined up on the side shelf. The dugout is lined, perhaps with heavy paper or tarpaulin. There are curtains at the windows.

There are two bunks in the dugout, possibly lined with corrugated iron. The top bunk has curtains for privacy.

The dugout from the outside - looking like home. It's a safe haven, different in style but similar in concept to Major Luxmoore's dugout.

A still life - a candle in scrap metal, a box of matches, his mirror, and a wine bottle with a glass, presumably for water.

The ruins of a church. The walls and roof have been destroyed, but Christ on the Cross survived the destruction.

This looks like a room in a farmhouse - but there are regular clips or studs on the ceiling suggesting it may be inside a well-established dugout. There are massive beams. There's a solid table - possibly a billiards table, some freestanding shelves, and a clock on the wall. And there's a rural scene that could be a makeshift mural on the walls to brighten the room.

Is this a self-portrait? It is unnamed, whereas later portraits are titled 'Gurkha' or 'Sikh' or 'Tomy'.

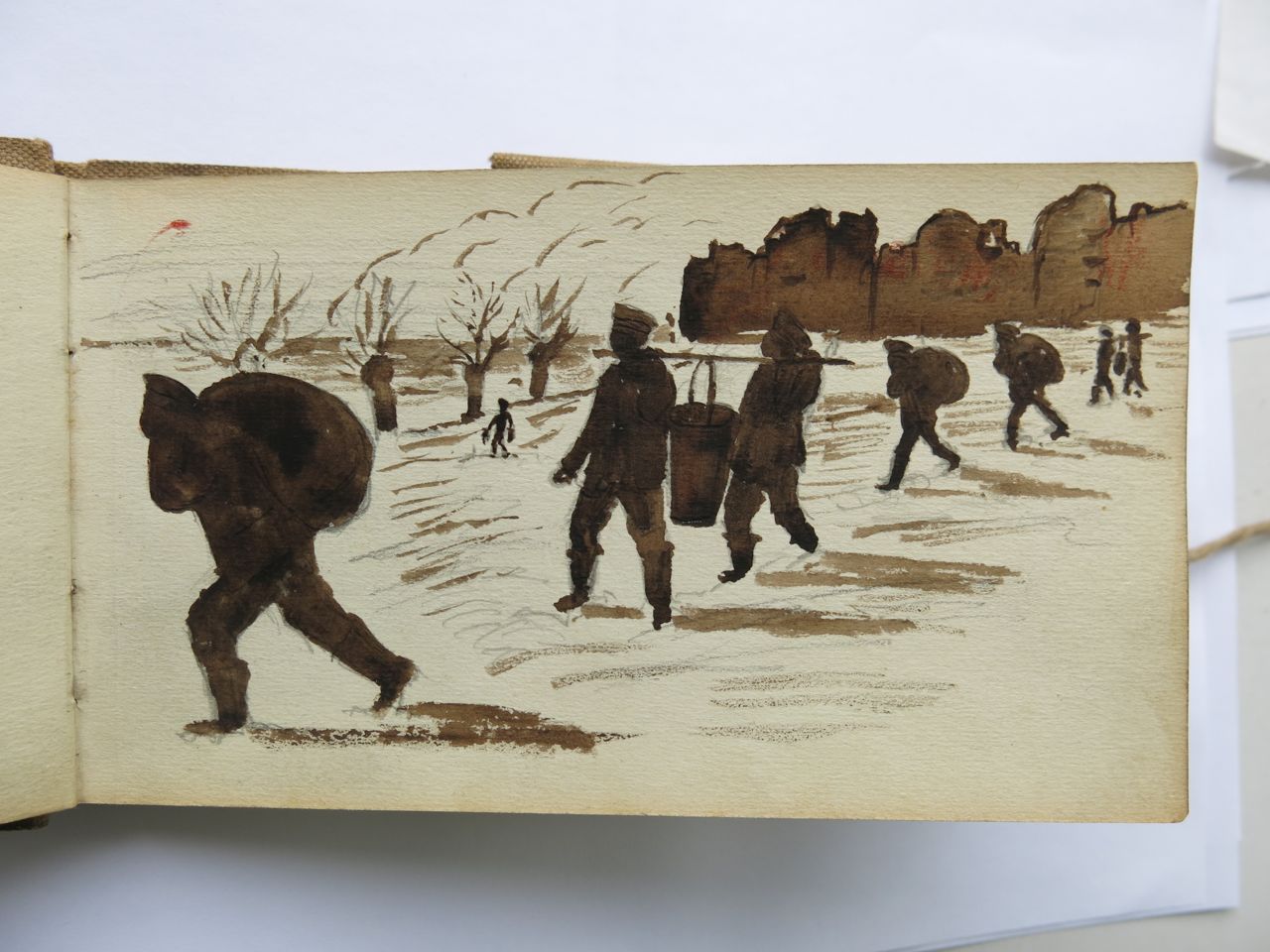

It's an interesting orientation for a profile. Perhaps Kolling was left-handed. Or he may have drawn it from his reflection in the mirror that features in several sketches.

So far, the sketches themselves are undated. It's clearly Winter. There's snow on the ground as the soldiers trudge back to their camp carrying sacks of coal from a ruined village.

I think it's coal they're carrying in those heavy sacks and that bucket.

In the far background are the outlines of the rolling clouds that I think represent war. Kolling develops the imagery as the sketchbook progresses.

Their reward is this blazing fire in a corrugated iron dugout. The walls of the dugout are lined.

There are glimpses of the countryside through the windows.

For me, this has a dreamlike or metaphoric quality. Is that a bomb falling on the unsuspecting village in the distance? It could be an observation balloon but the perspective looks wrong and it should be tethered to the ground. The rolling clouds of war have colour and emotion, backlighting the simple innocence of the village, where smoke rises peacefully from the chimneys.

The heroic figure on the horse is larger than life, leading the troops in well-ordered lines of marching soldiers.

There is a sense that the cause is noble and good.

The furnace with a meagre stockpile of wood.

This is dated 20 Mar 1915.

The roof of the church has been destroyed. A building nearby goes up in flames. The rolling clouds of war hover in the background.

There's an inscription written in German. Please help with interpreting it if you can.

Kolling served with the German Field Artillery. A farmyard barn.

A much rougher dugout, with duckboards across the mud.

This is dated 26 November 1915.

My interpretation is below.

Kolling strolls along in the sunshine, smoking a cigarette, hands in his pockets. He is relaxed and happy, no weapons in sight.

The laughing sun peeps out from behind the clouds of war, suggesting a dream or wishful thinking.

The world is bright and shining, the fields are green, the buildings undamaged.

The war is coming to an end.

And then comes the harsh reality.

Kolling is brought back to earth with a thud, metaphorically or physically.

He lies in the mud, struggling to get to his feet.

The setting is the same, with the cobblestones and the corner of the building with windows, but the distant scene is messy and bleak.

The sun still laughs - but mocking him now.

The war is not over. . .

It's a few days before Christmas - 20 December 1915.

As they move through the countryside they see damaged farmhouses. The ever-present clouds of war are lightly sketched in the background.

The place names look interesting - but indecipherable to my Australian eyes.

This is around Christmas Day 1915. I assume from K5 that Christ on the Cross was significant to Kolling. This was an emotional time for him.

The clouds of war are intense and tumultuous, threatening to overwhelm the world around him.

The tumult has passed, leaving devastation in its wake. Yet the fields are still green and the sky is blue. There is hope.

A new sanctuary, perhaps in a ruined farmhouse. There is a roaring fire and a sense of normality.

I cannot pick the tone of this portrait. The exclamation mark suggests it is humorous or satirical.

A still life of guns and ammunition, laid aside.

This celebration is dated 6 January 1916.

There's a small Christmas tree. The gun lies casually on the shelf.

The mirror and the candle in its trench art candleholder are still there from K4.

And now there is a feast - cheese and tomatoes on slices of rye bread, with a bottle of wine waiting to be opened.

Another still life - a box of matches, an ashtray, and a lit cigar. A moment to enjoy.

A work in progress. Like the Gurkhas that follow, it may be out of sequence - experimental sketches towards the back of the book.

These sketches of Gurkha POWs are gentle portraits. They show respect for the enemy.

The Gurkhas fought the Germans fiercely at the Battle of Loos, suffering huge casualties. Some were taken prisoner of war.

Kolling portrays the Sikh as a kindly man holding his head high, rather than an enemy to be humiliated or belittled.

_ _ _ _ _

It echoes the attitude of Capt Henry Ogle towards his German opponents. In his Journals Ogle describes an event where one of his men received a DCM, and the Croix de Guerre from the Belgians.

' . . . Then we brought in the dead German. We laid him on a stretcher and had him carried down to Battalion Headquarters. There was a little cemetery at Wulverghem and there we gave him a proper military funeral.' (p44).

The trees are bare. It's Winter again. There are damaged roofs.

Kolling's 'puppchen'.

Kolling is still on active service, so this is most likely a farm dog he has befriended.

In the midst of war, this contact with innocent animals was important.

Captain Ogle writes in his Journal -

'Once again we saw and talked to women and children, cats and dogs. Some even found cows and horses and talked to them.' p118

A still life - the end of the day?

His rifles lean against the wall. His greatcoat hangs neatly from a hook. His helmet sits on the shelf.

A suitable ending to a wonderful sketchbook.

Is this a self-portrait?

Perhaps it is drawn from his image in the mirror.

K7 wears glasses but the orientation is the same.

This is the only page that is loose.

Elsewhere, 3 pages have been neatly cut from the sketchbook, leaving a thin stub.

Please help decipher this.

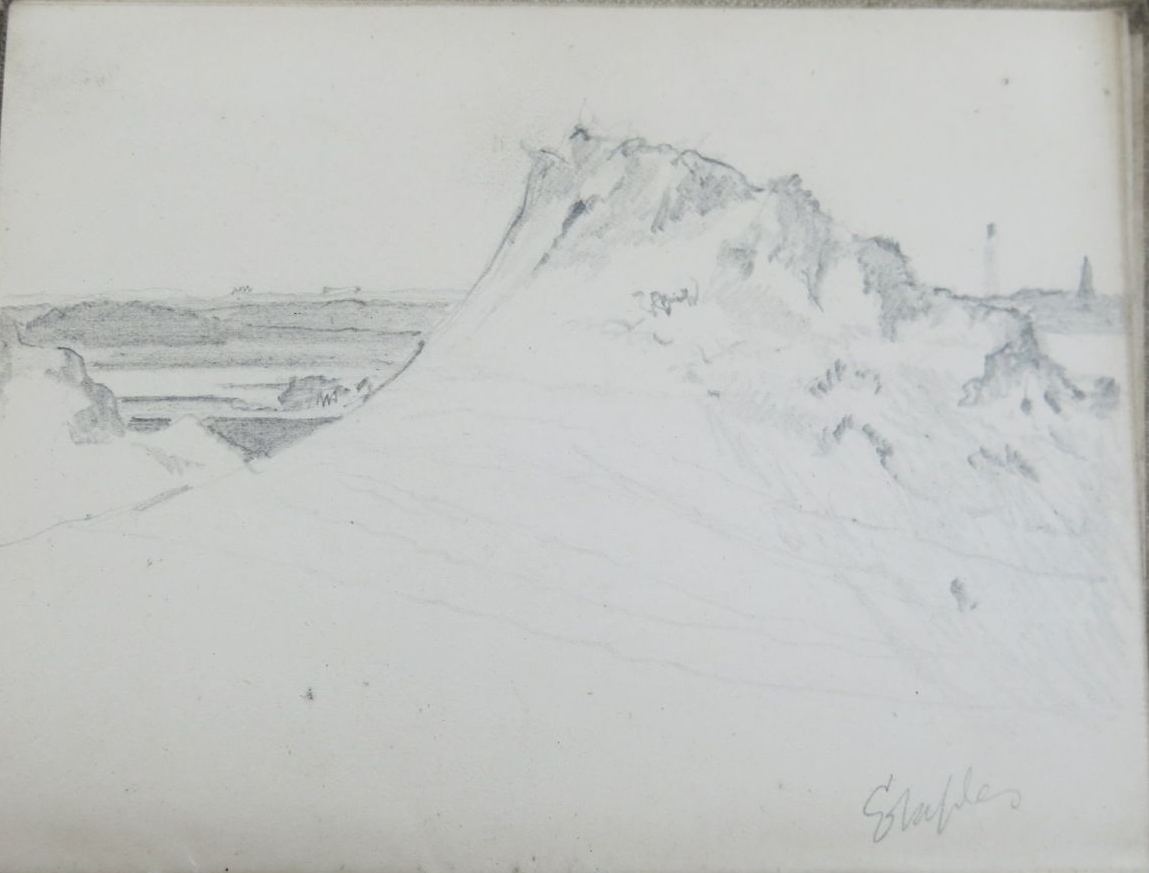

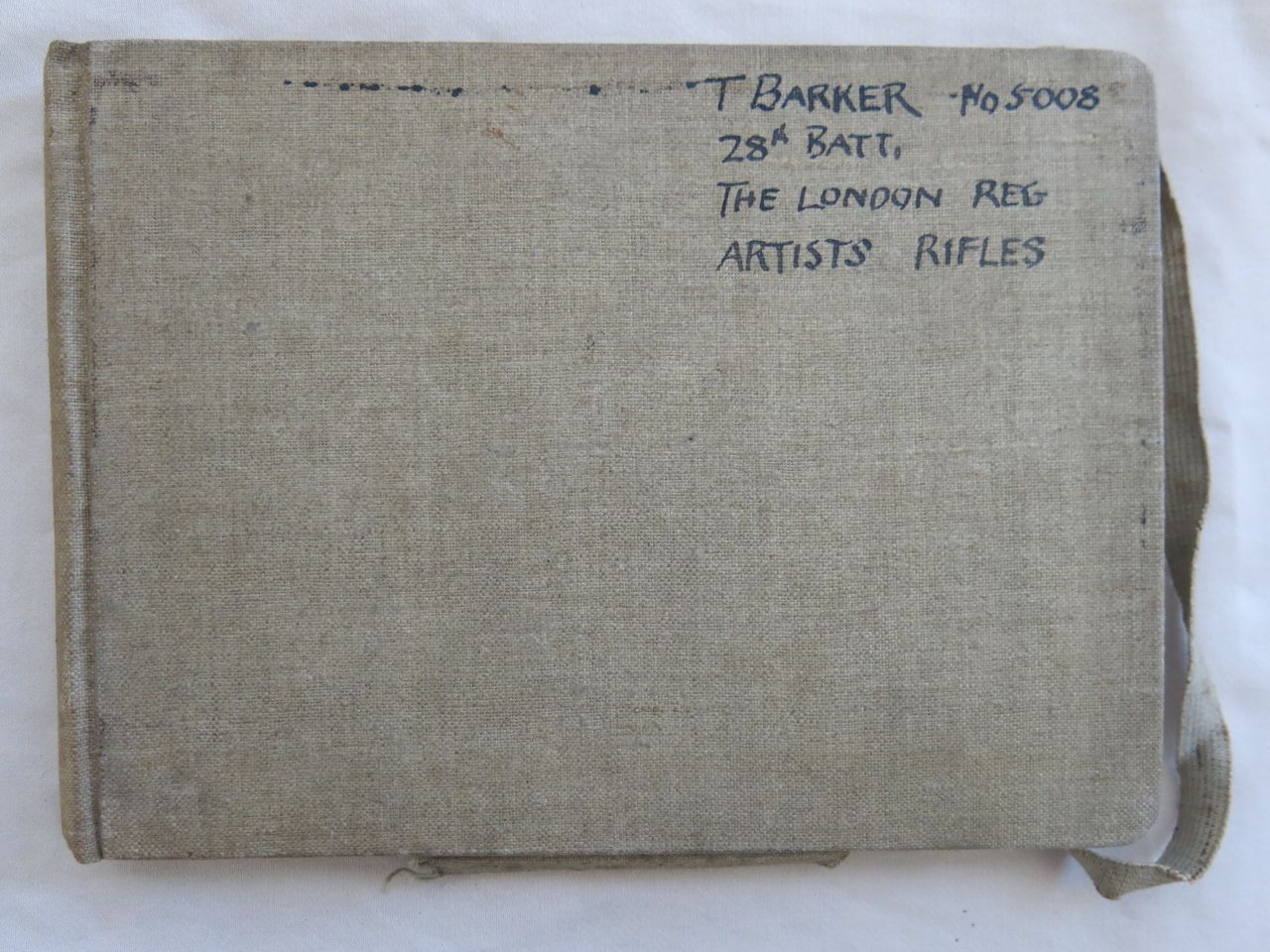

Theo Barker studied at the Royal College of Art and went on to become an Art Teacher.

This sketchbook comes from his time with the Artists Rifles, and then the Manchester Regiment, on the Western Front near Etaples and Hesdin.

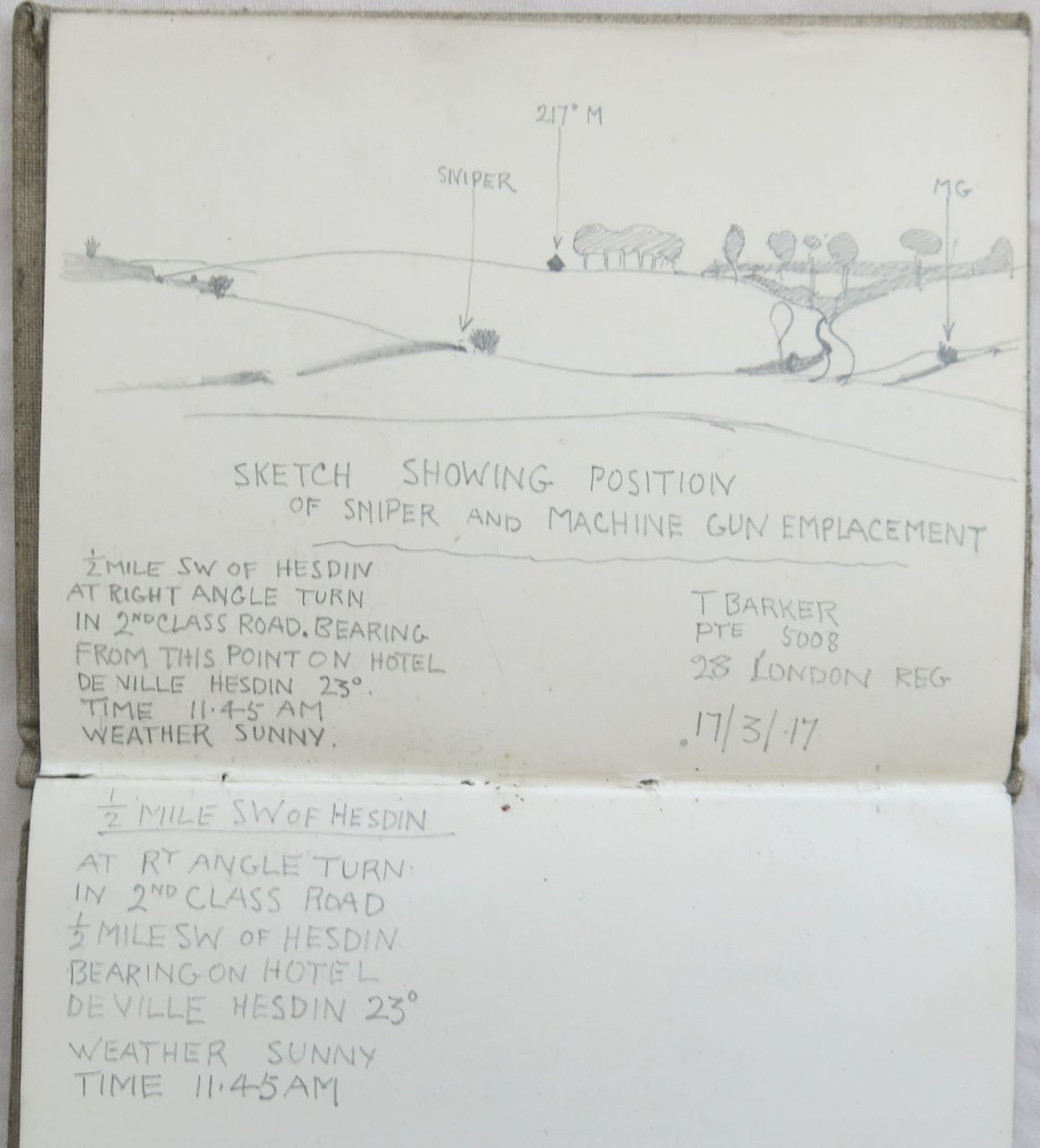

He was killed in action a few weeks later, on 13 May 1917. The final sketch is a map showing the position of a sniper on the outskirts of Hesdin.

The sketchbook is part of an extensive collection of letters and personal documents belonging to the Barker family. The story of Theodore and his brother Norman will be told in Ephemera, later.

The sketchbook is small - 14cm by 10cm. It is described inside as a SKETCHERS' NOTE BOOK, Containing 80 Leaves of Good White Paper.

Handwritten inside is the date Oct 26th 1916.

Theo Barker was killed in action on 13 May 1917.

The first page is a list of place names on the Somme, presumably where Theo served between 26 October 1916 and his death at Bullecourt on 13 May 1917.

Ypres, Armentieres, Laventie, Vielle Chapelle, Baileul, Merville, Poperinghe, Hinges, La Gorgue, Sailly, Vermelles, Bully, Souchez, Ecurie, St Aubin, Arras, Bernaville, Gommecourt, Wattan?, Steenvoorde, Nieppe, Fleurbaix, Fauquissart, Grenay

The long, long list of battles - and then this. The first sketch is of a cart horse waiting patiently as its load is upended.

In the midst of war, there was comfort and reassurance in observing the mundane life of farm animals. Ogle remarked on it in his journals; Kolling painted a puppy. This was the life they chose to think about, a way perhaps to retain their sanity in a world of madness.

There are a number of sketches of Hesdin, including a significant one at the back of the book showing the position of a sniper.

Note: Unlike other sketchbooks in this collection, the order appears to be random. There are many blank pages interspersed between sketches. They are presented here in the order they appear in the book.

This could be a self portrait. There are similarities with the portraits of Theo Barker.

There's the suggestion of a figure leading a horse and cart along the road into the village. That could be sea in the distance beyond the dunes.

There's a vague outline of two horses at the end of the road. Like many of the sketches, it is unfinished.

This sketch was made a few weeks before Theo was killed.

Paris Plage features in Henry Ogle's journals during his time at Etaples. He writes 'The seaside resort of Paris Plage was only a tram ride away and one afternoon I thought of a possible sketch on the beach. The tide was out, far enough to be able to visit the wreck of a cargo steamer . . . I managed to make a very slight sketch of it before the tide made me leave the beach' (p154).

The notation on Theo's sketch suggests he was stationed at the Number 1 Training Camp at Etaples. And that he could see the beach from camp.

Note: there is an enigmatic squiggle in the the bottom corner of the right hand page - ????? Room?

Hesdin Forest

Theo Barker ran training sessions in military map-making. Here he has used his sketchbook to illustrate some points.

1/2 MILE SW OF HESDIN AT RIGHT ANGLE TURN IN 2nd CLASS ROAD. BEARING FROM THIS POINT ON HOTEL DE VILLE HESDIN 23 (degrees).

TIME 11.45 AM

WEATHER SUNNY.

T BARKER PTE 5008 28 LONDON REG 17/3/17

DRAWN AT A POINT AT RIGHT ANGLE TURN IN 3RD CLASS ROAD, 1/2 MILE SW OF HESDIN 200X FROM MAIN ABBEVILLE AT ST AUSTREBERTHE

TIME 2.50

WEATHER SUNNY

T. BARKER PTE 5008 28TH LONDON REG 17.3.17

note any peculiarity in the neighbourhood of point noted.

use sketch to show any special point - (window)

Type of Field sketching

Exaggerate objects - as spire etc

plenty of space top & bottom of sketch

22nd Batt M/C

C.R. Howell 8th Lincolns

T. Barker A Coy 1st Batt Artists Rifles

1045

Goss

Borthe?

Guermond?

???

The Artists Rifles drew many of their recruits from universities. Many were used as trainers.

Theo Barker's particular skills were in modelling and map-making. He appears to have run training sessions in the field, using resources like this technical notebook.

(He also had a cardboard template for coding messages; this will be featured in his story in Ephemera, later.)

This is a 'sketchbook' of tracing paper 18cm by 13cm. Each page is ready to be torn out along a dotted line.

This particular book has been used as a training manual for military map-making.

A photo shows through the tracing paper. A topographical map could be traced showing features and the terrain, then torn out to be reproduced and circulated.

This is a comprehensive set of symbols for features of military interest - from roads and bridges through to canals and weirs and fords, railways and tramways, bridle paths and footways, churches, chateaux, obstacles, woods, forts, ruins, entrenchments, observation posts, telegraph, lighthouses, watermills, wells, mines, farms and signposts.

A sample military map, presumably for teaching purposes. Note: a sheet of white paper is temporarily placed behind the tracing paper to show the outlines clearly, in this and subsequent pages.

Method of using protractor in making sketch map from bearings taken by means of compass & by pacing out.

A brick & stone bridge crosses a railway. The railway at this pt runs thro a cutting. The pathway is 20' above sea level. The bearing of the railway is 40 (degrees) Mag. The diameter of the contour taken on the bearing of 40 (degrees) mag is 300x & the width of contour at rt angles is 115x.

100 yds = 1"

width of Bridge 8 yds

road of Railway 30 ft

The sketchbook and training notebook are part of an extensive collection of letters, photos and diaries belonging to Theo Barker and his younger brother Norman.

It is a rich and emotional story. It will be told in Ephemera, later.

Theo sent this postcard to his brother Norman, who was also a serving soldier, at the end of April 1917.

It arrived on 3 May 1917.

Ten days later, Theo was killed at Bullecourt.

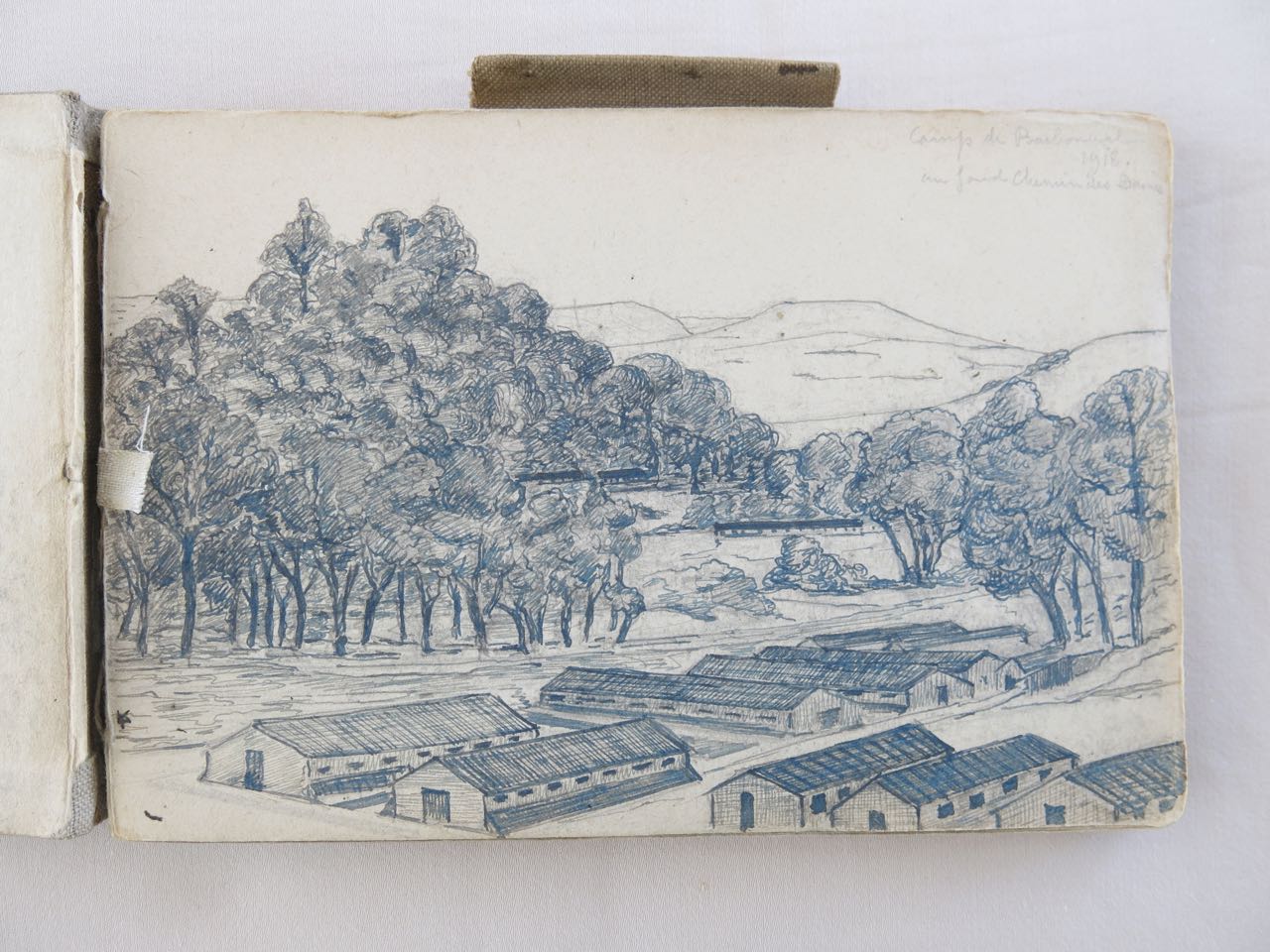

It appears that the sketchbook belonged to a French officer who served at the Battle of Yser in 1914 - 15. He served again near Chemin des Dames in 1918 until he was taken prisoner of war by the Germans. He was held in POW camps at Rastatt and Osnabruck until the end of the war.

The sketchbook is in two parts separated by many blank pages. The 1918 Osnabruck sketches are at the end of the Yser 1914-15 section, in the same style. The Osnabruck sketches also show the same fine penmanship as the Rastatt 1918 sketches, suggesting they are by the same artist.

Osnabruck was a German POW camp for French officers.

- - - - -

The sketches start from the back of the book, upside down, as if the artist is practising before starting at the front. There are two sample header pages for L'YSER LES FLANDRES 1914 - 1915, presumably rough ideas for the front of the book.

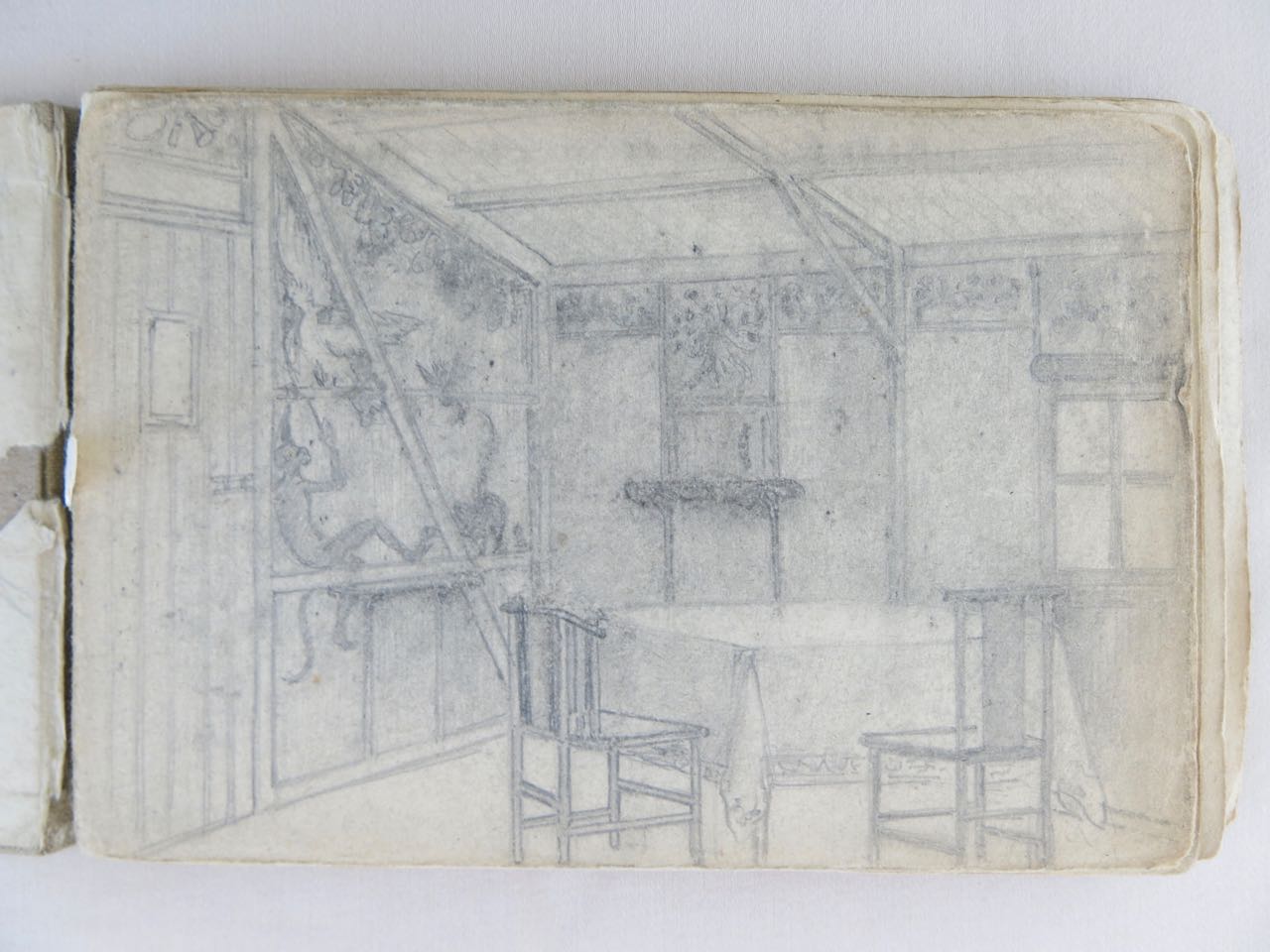

There's the cosy interior of what looks like a farmhouse, with an exotic wallpaper or mural on the wall. There are practice sketches of monkeys and parrots. Perhaps the farmhouse is drawn from memory.

The front of the sketchbook starts with Chemin des Dames 1918, and continues through Rastatt and views over Baden 1918.

Osnabruck 1918 is the same orientation as these, but on the white pages at the end of the book.

All annotations are in French. There is no name.

Comp de Bouconval?

1918

au fond Chemin des Dames

This is written in pencil in the top right hand corner of the sketch. The name of the camp is very faint and hard to decipher.

- - - - -

This is the first sketch in the front of the book. The page is loose, but there are matching smudges inside the front cover from the heavy pencil shading, suggesting that's where it belongs.

Sur Chemin des Dames

de l'Eglise de Paissy

The church sits atop the hill at Paissy overlooking a tree-lined row of houses and peaceful cultivated fields.

- - - - -

There are photos showing this church in ruins in 1916. This sketch is undated, unlike may of the others. Perhaps this was drawn during his time in Flanders, intended as the first 'proper' sketch at the front of the book, after the title page L'Yser les Flandres 1914-1915 that he was still practising.

As events overtook him, the formal title page was abandoned, replaced by the camp at Bouconville 1918. The sketches that follow are from the German POW camp at Rastatt dated 1918.

L'Eglise de Paissy belongs to the earlier period, after the Battle of Yser.

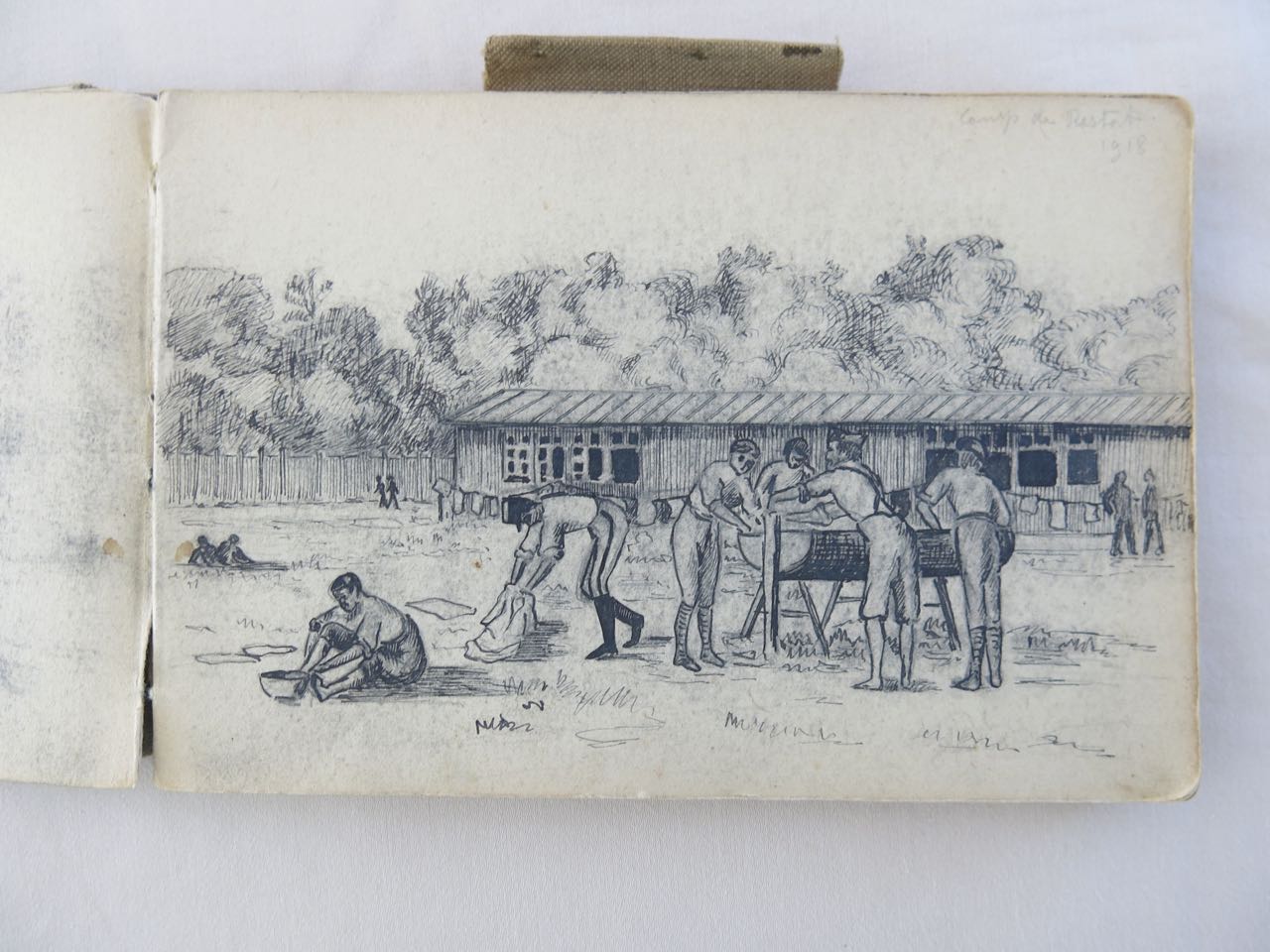

These sketches are from a German POW camp at Rastatt near Baden.

This is a German prison camp, but the mood is peaceful. The prisoners are relaxed, washing their clothes in the sunshine. There is no sense of threat.

Once again, the mood is relaxed.

Perhaps it helped to see the world this way - as a group of comrades enjoying each others company. Art therapy in trauma.

There is no sense of menace even though there are armed guards outside and they are in enemy territory.

Comp de Rastat 1918

I cannot decipher the very faint pencil script under 'Comp de Rastat 1918'.

This is clearly inside the prison camp, based on the following sketches.

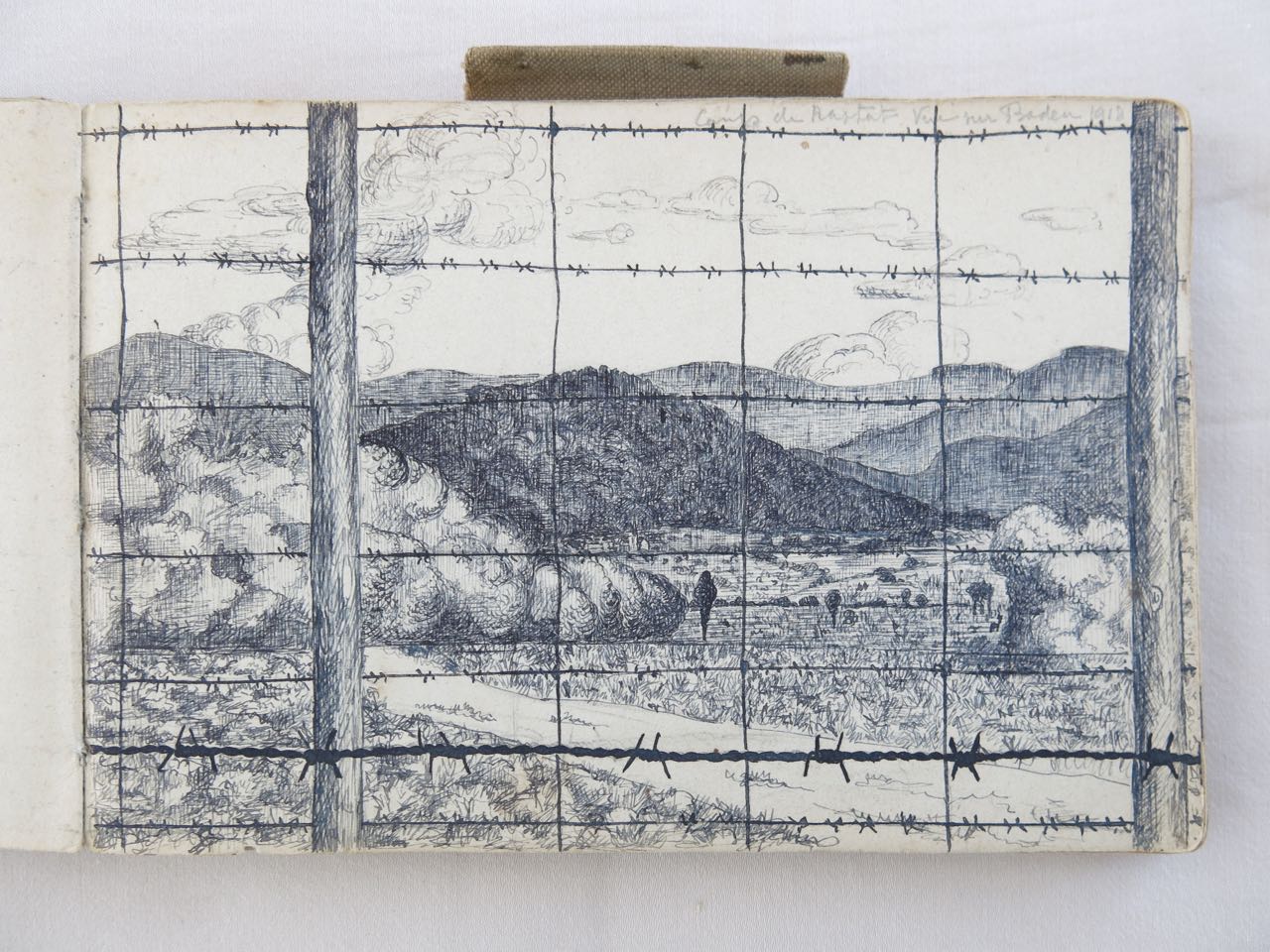

The fine penmanship shows the meticulous symmetry of the German fencing.

The mountains are still there, behind the layers of barbed wire.

It's the view outside the prison camp that draws the artist's attention. He sees the beauty of the landscape even through the barbed wire that holds him prisoner.

That's what he chooses to think about.

Comp de Rastat

vue sur Baden 1918

He is still a prisoner of war. He draws strength from the beauty of the countryside, through the barbed wire.

Comp de Rastat 1918

vue sur Baden . . .

There is an undecipherable phrase after 'Baden'. This is from a different angle - there are powerlines here.

This is the final sketch in this section. There are many blank pages before the camp at Osnabruck 1918.

Osnabruck was a German POW camp for French officers.

The artist is still a prisoner, judging by his attire in the self portrait.

The war is nearly over. He is at peace, still seeing the beauty of the world around him.

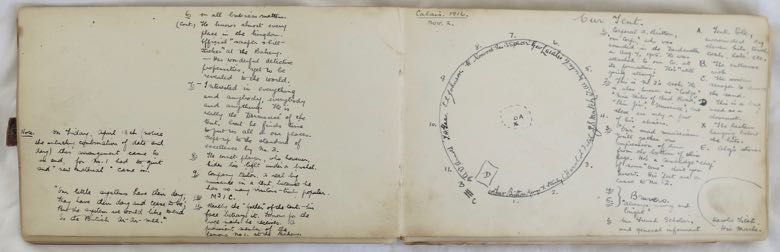

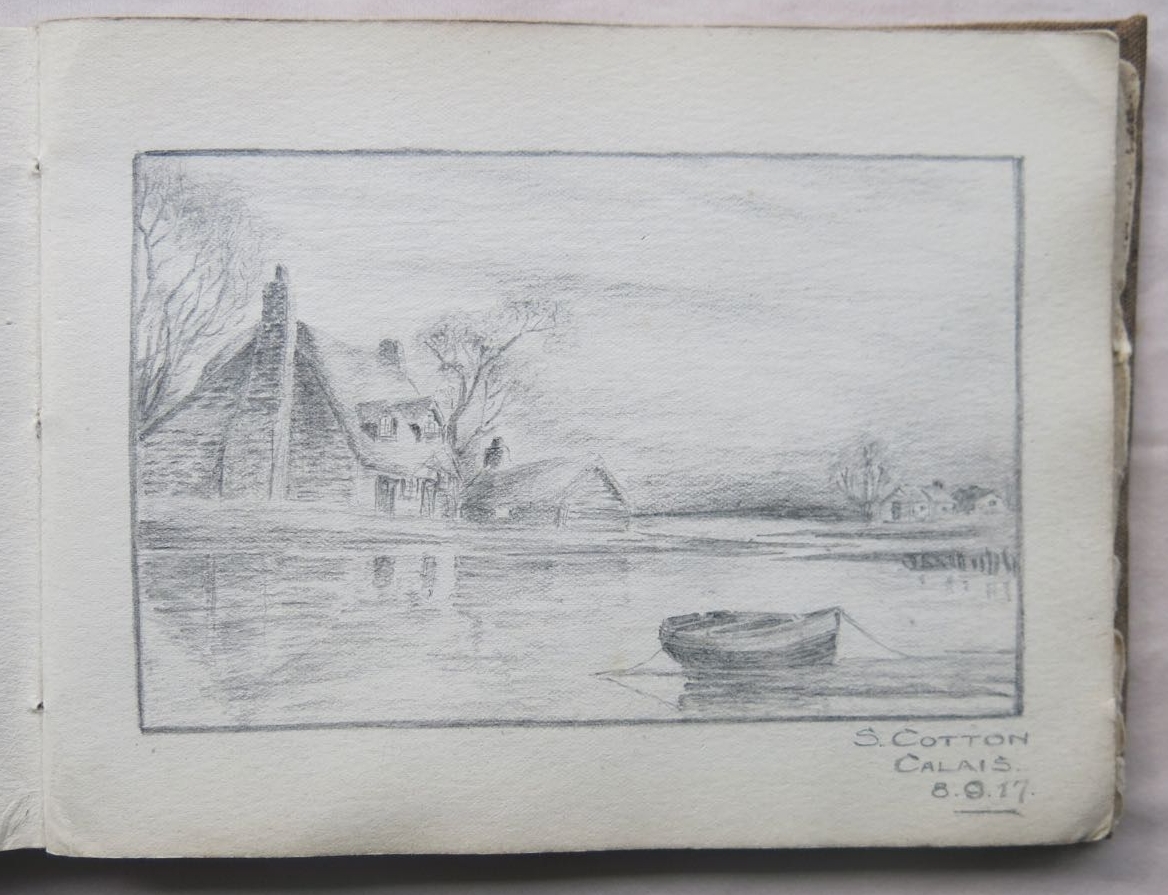

This collection of five books belonged to George Victor Stanley, a conscientious objector who served in France in WW1.

The closed books - his autograph album and his book of woodcuts - belong in Ephemera.

The open sketchbooks are important. They record the experience of a group of conscientious objectors who volunteered to serve in the field but not to bear arms.

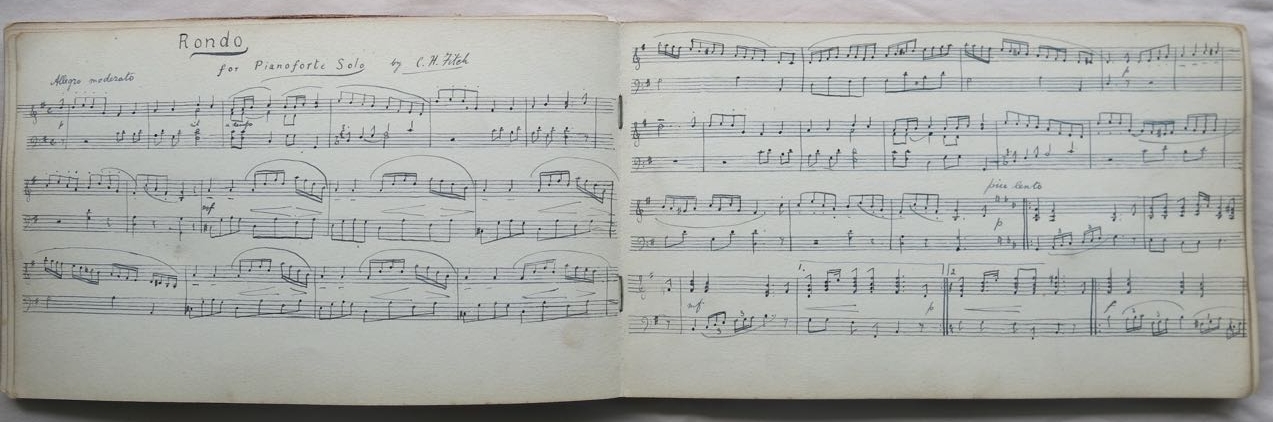

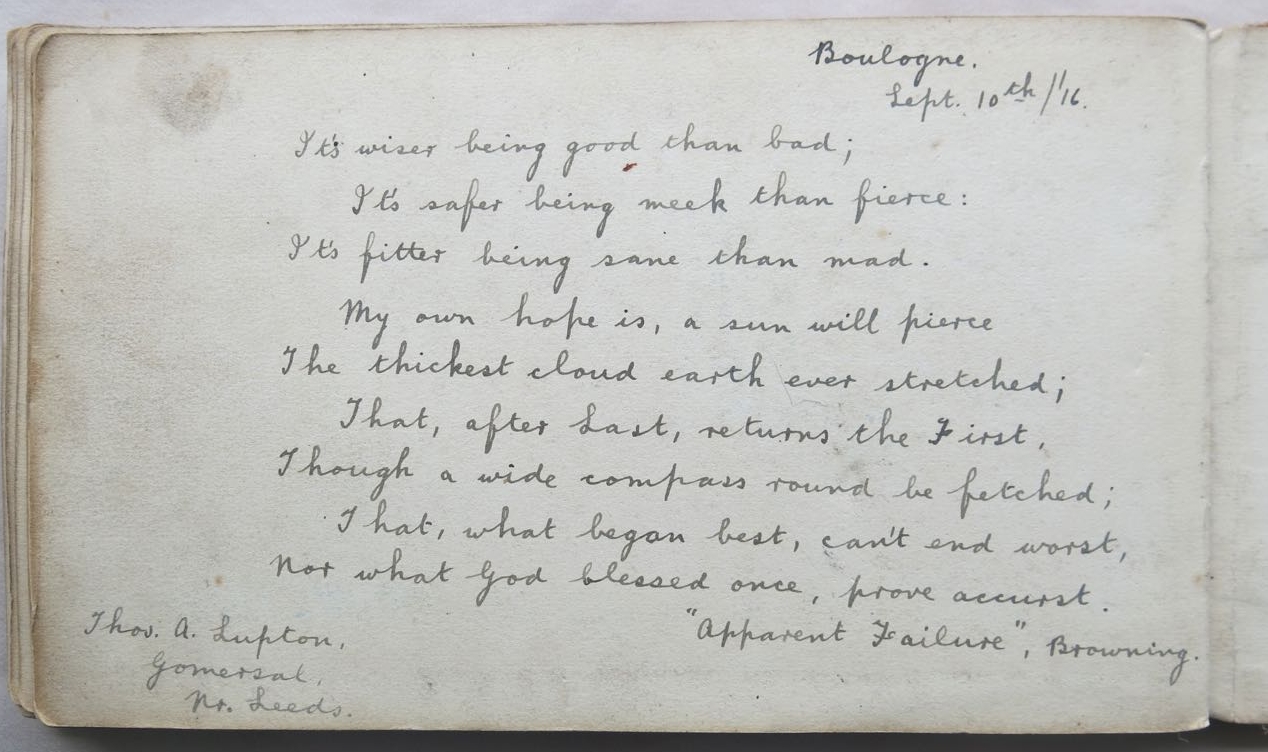

They worked enthusiastically in a bakery at Calais for over a year, providing food for troops entering France or leaving wounded. Two of the sketchbooks cover that period, with C.Harold Fitch writing music and George Stanley leading the team and maintaining morale. Morale was important - it was a time when conscientious objectors were often ridiculed as cowards.

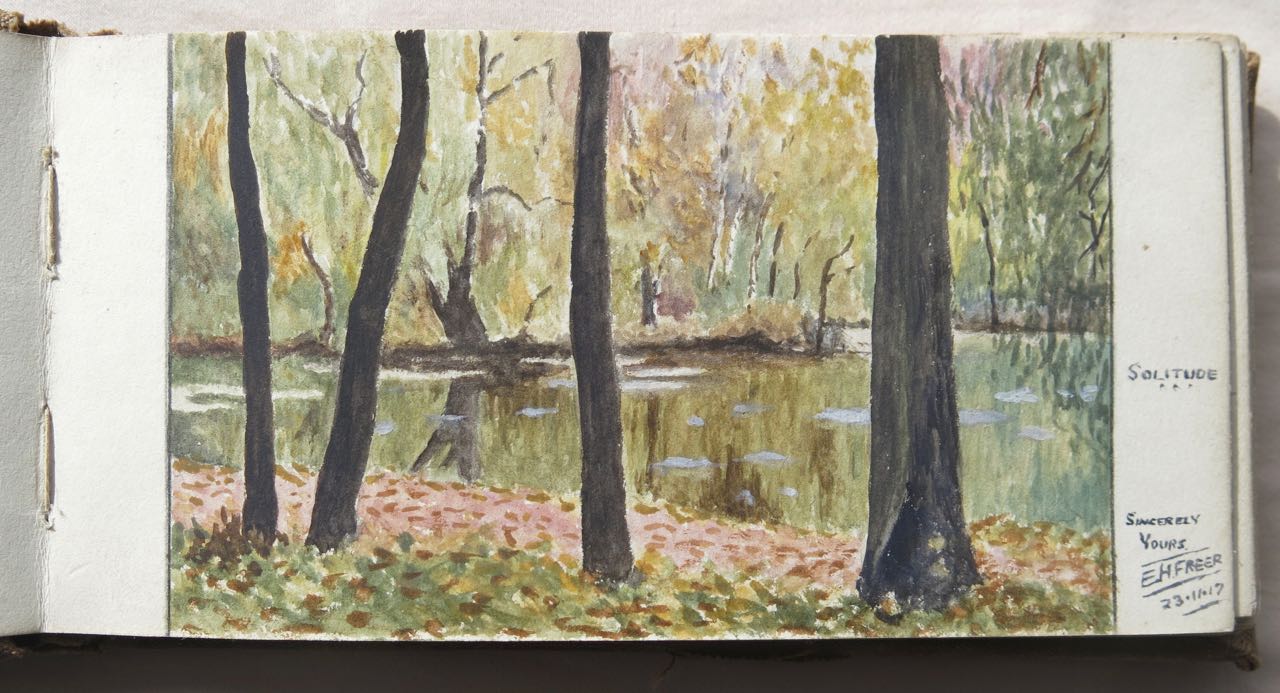

It's not clear how it happened, but the group ended up in the prison camp at Blargies, on the line between Amiens and Rouen. One of their number, young Ernest Freer, was arrested for refusing to handle barbed wire - which he viewed as a weapon, potentially causing death. A few weeks later, one by one, his mates were ordered to load barbed wire. One by one they refused. They were arrested and sent to the courthouse at Abancourt to await court martial.

Potentially, they faced death by firing squad. An earlier mutiny at Blargies by ANZAC soldiers led to the execution of two New Zealanders.

George Stanley circulated the sketchbook that held Freer's painting 'Solitude' among those awaiting court-martial. On the front page he exhorted them all to write something - to leave a permanent, passionate record of what they believed in, and what they were prepared to die for.

And they did.

The 'Solitude' book is the result.

In later life, George Victor Stanley became headmaster of Nottingham School, with a talent for woodcuts. C. Harold Fitch followed in his father's footsteps and became vicar of Melton Mowbray. He made a name for himself as a specialist in English dialects, and had a passion for music.

These two men were conscientious objectors.

On 7 December 1917 Stanley and Fitch were in the Guard Room at Abancourt, on the line between Rouen and Amiens. They were there to support 15 young men of the 2nd Northern Coy NCC (Non Combatant Corps) who faced court martial and the possibility of the firing squad.

This was a tight-knit group. They'd served together for 18 months, mainly in Calais and Boulogne. They refused to bear arms, but served in any way they could outside of fighting. Many had stated a preference for the RAMC on their enlistment forms, knowing they could come under fire as stretcher bearers. In reality, they worked in a bakery at Calais, providing food for troops entering France and the wounded returning home to England.

Morale was tremendously important.

Stanley and Fitch worked on maintaining morale. Stanley kept 3 sketchbooks from that time.

The first - the Red Book - would not be out of place at a management retreat in 2017. There are team building exercises where strengths and weaknesses are on humorous display. There are sheets of music from C. Harold Fitch. Towards the back there are 49 signatures - names and home addresses of the young men of the NCC.

The second book - the Grey Book - has entries from the NCC at Calais. There are poems, sketches, cartoons and quotes - all signed with name and address.

It is the third book below that is the most important.

This small grey sketchbook is a book of beliefs - written and signed by young men whose lives were on the line. They faced court martial for refusing to handle barbed wire, which they saw as a weapon of war.

One by one, on 7 December 1917, they wrote in the book and signed their names - saying in effect 'This is what I believe, this is what I am prepared to die for.'

This double page spread is George Stanley's description of those in his tent at Calais.

What follows is a transcription of Stanley's comments.

Note: Many of those listed have contributions in all three sketchbooks. Names, addresses and service numbers, with available enlistment details, will be added later.

1. Arthur Britton

Corporal A. Britton, "our corp.," who was wounded in the Dardanelles on Aug. 7, 1915. He was attached to our Co. at its formation. He's "still going strong".

2. George V. Stanley

This is No. 2's book (George Stanley himself). He is also known as "Codge", "Nine Miles of Bad Road", "Slim Jim", "Nuisance"; but these are only a few of his aliases.

3. C.Harold Fitch

"Our" mad musician. You'll gather one impression of him from the bottom of this page (his thumbprint). He's a Cambridge "chap" of some "tone", don't you know.. His feet are a curse to No. 2 (the writer George Stanley).

4. J.S. Mutch

5. T.W. Mutch

"Bruvers" "Always merry and bright".

6. Geo Laedles?

Our French Scholar, and general informant on all business matters. He knows almost every place in the kingdom. Official "scraper and bill-sticker" at the Bakery. His wonderful detective propensities yet to be revealed to the world.

7. Geo 3 Spencer

Interested in everything and anybody, and everybody and anything.He is really the "Dormouse" of the tent, but he finds time to put all of us in our places. Kept up to the standard of excellence by No 3 (Cambridge undergrad C. Harold Fitch).

8. W. Norwood

The cornet player , who, however, hides his light under a bushel.

9. E.L. Johnson

Company tailor. A real big nuisance in the tent, because he has so many visitors - truly popular.

10. T.H. Gee

M cubed I C

11. A.V. Arnold

Really the "father" of the tent - his face betrays it. Famous for the large mails he receives. A prominent member of the famous No. 1 at the Bakery.

Note: On Friday, April 13th (notice the unlucky combination of date and day) this management came to an end, for No. 1 had to quit and 'new material' came in.

"Our little systems have their day;

They have their day and cease to be;

But the system we would like to end

Is the British Ar-Ar-Mee."

Later in the red book is this double page spread of names and addresses of those in the NCC.

The story behind this sketchbook is told in the blog ‘2nd MUTINY AT BLARGIES?’

This is a tiny sketchbook - a mere 4" by 2.5" or 10x6cm. It is tattered and a bit dog-eared. The covers are long gone.

It belonged to Private Leonard Alfred CUTT G8/24698 of the Royal Fusiliers.

The sketches are from August to October 1918, in France.

There's no doubt he saw the heat of battle - the graphic images show the fury of 'the barrage of Sep 1918'.

He dreamt of simple things. His roast beef with vegetables and gravy is mouthwatering in August 1918.

His football game of 1918 is on burnt and devastated ground.

Interspersed with the battle scenes are peaceful sketches of the countryside. There are quiet observations of the people he sees, like the woman waiting by the fireside, and the Chinese Labour Corps.

Leonard Cutt survived the war. He married in 1926 and died in 1974 at the age of 82.

Note: this is out of sequence.

France 12.8.18

6.9.18 France

Note: the symbol in the horseshoe is the insignia of the Royal Fusiliers.

26.9.18

14.9.18 France

Why is it the boys are running?

What is it that makes them cheer?

Is it the letter call that's sounding

Telling of news from loved ones dear.

15.9.18 France

15.9.18 France

26.9.18 France

25.9.18

11.10.18

15.10.18

18.10.18 France

©2016 Judy Waugh